The Noise of the Flag | Part II

Only the wisest prophets knew that it was only the end of the first act of the long, long drama… S. M. (pp. 87, 89)

Video from RTÉ Archives: 15,000 March in Derry – 16/11/1968

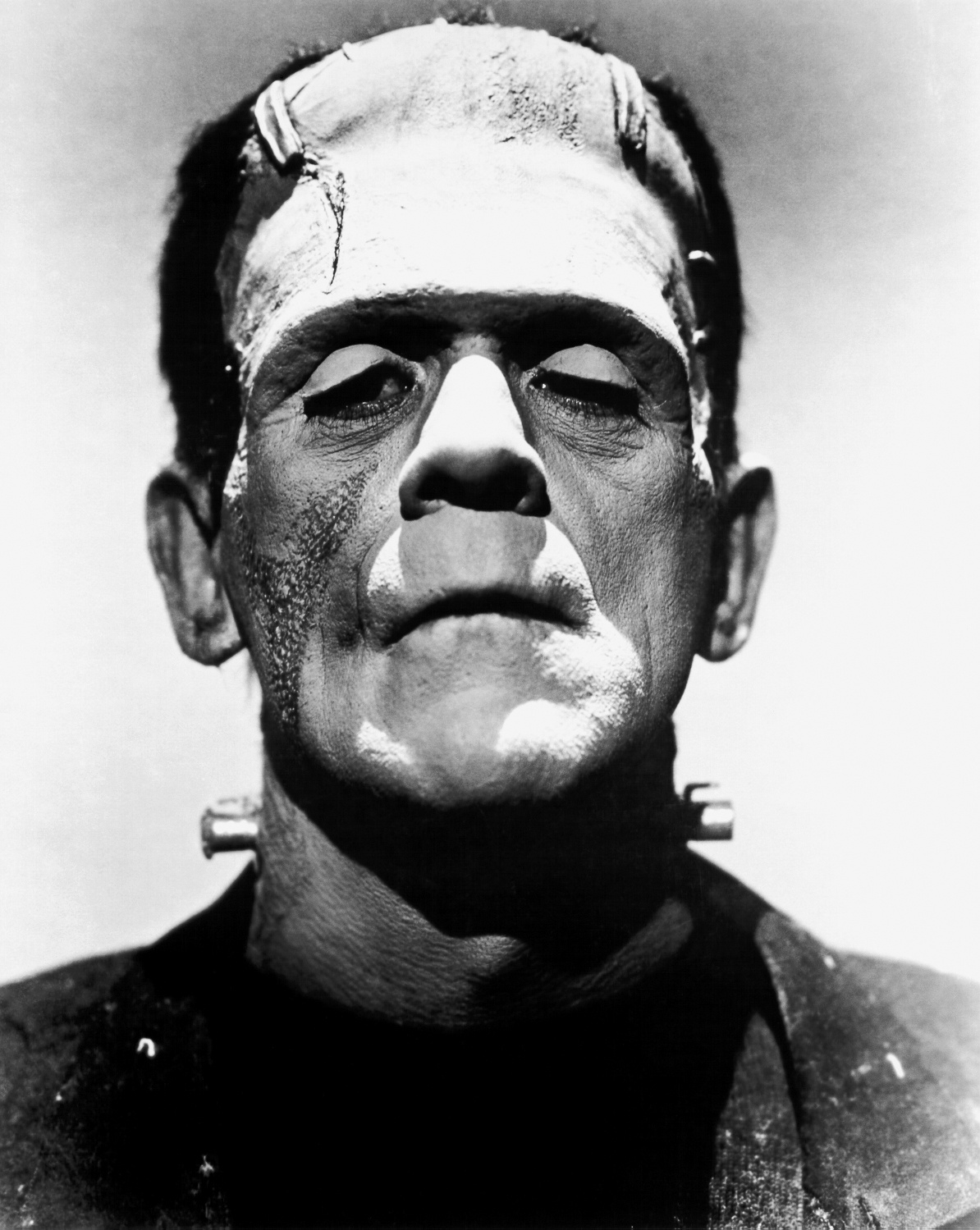

When I thought of myself as much more adult, instead, I had almost no reaction to his second operation. I opened the door and he was standing, proud to show me his Frankenstein-like suture… the new metal staples.

His pride came from the fact that, besides being a doctor and researcher, he had also become a case for the advancement of science.

… to hold a ‘long march’ of seventy-five miles from Belfast to Derry… Most members of NICRA were against it… Still they marched, avoiding with difficulty and re-routings set pieces of antagonism from Paisleyites who had harassed them from the outset when they began their journey at 9am on New Year’s Day 1969. The march was legal – O’Neill refused to ban it – so the students were under the grudging protection of the RUC, or so they thought.

On the morning of 4 January the marches left the village of Claudy and headed down the main road to Derry. They were joined by some supporters and numbered seventy by the time they reached Burntollet Bridge, about eight miles from their destination. They were advised by the RUC that a gang was gathered in nearby fields but they accepted the police assurance that they might just manage to get through. That was the impression the marches gained but in fact they were being led into a well-organised ambush. … The marchers were hailed with these bottles and stones. When some tried to escape into the fields nearby they were driven back on the road by policemen using batons. S. M. (pp. 90-91)

He actually tried to show us the video of his operation at lunch.

Today perhaps I understand. When one is subject of the surgical tools, they are no longer frightening.

At the time, the attempt to show us the operation video (my mother was against it; but my sister was starting to be like him) brought me the same discomfort as always. Weakness in the limbs and incapability of doing the task at hand, eating lunch at the table.

Because, unfortunately, this happened regularly, certain discussions about their patients and about various cases always took place at the table.

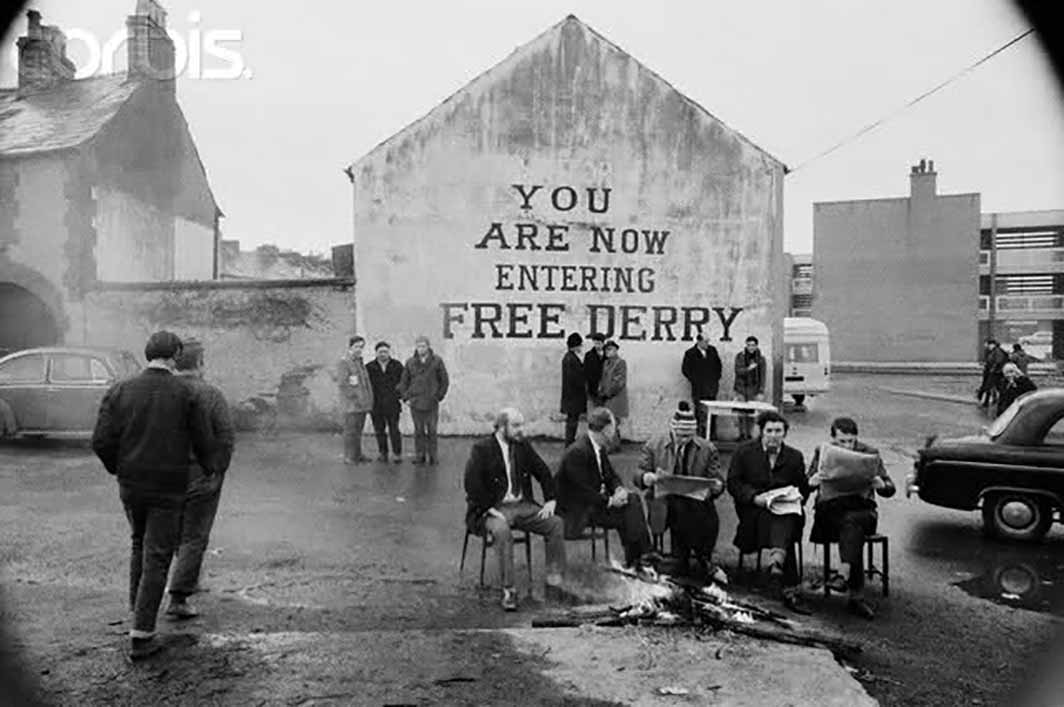

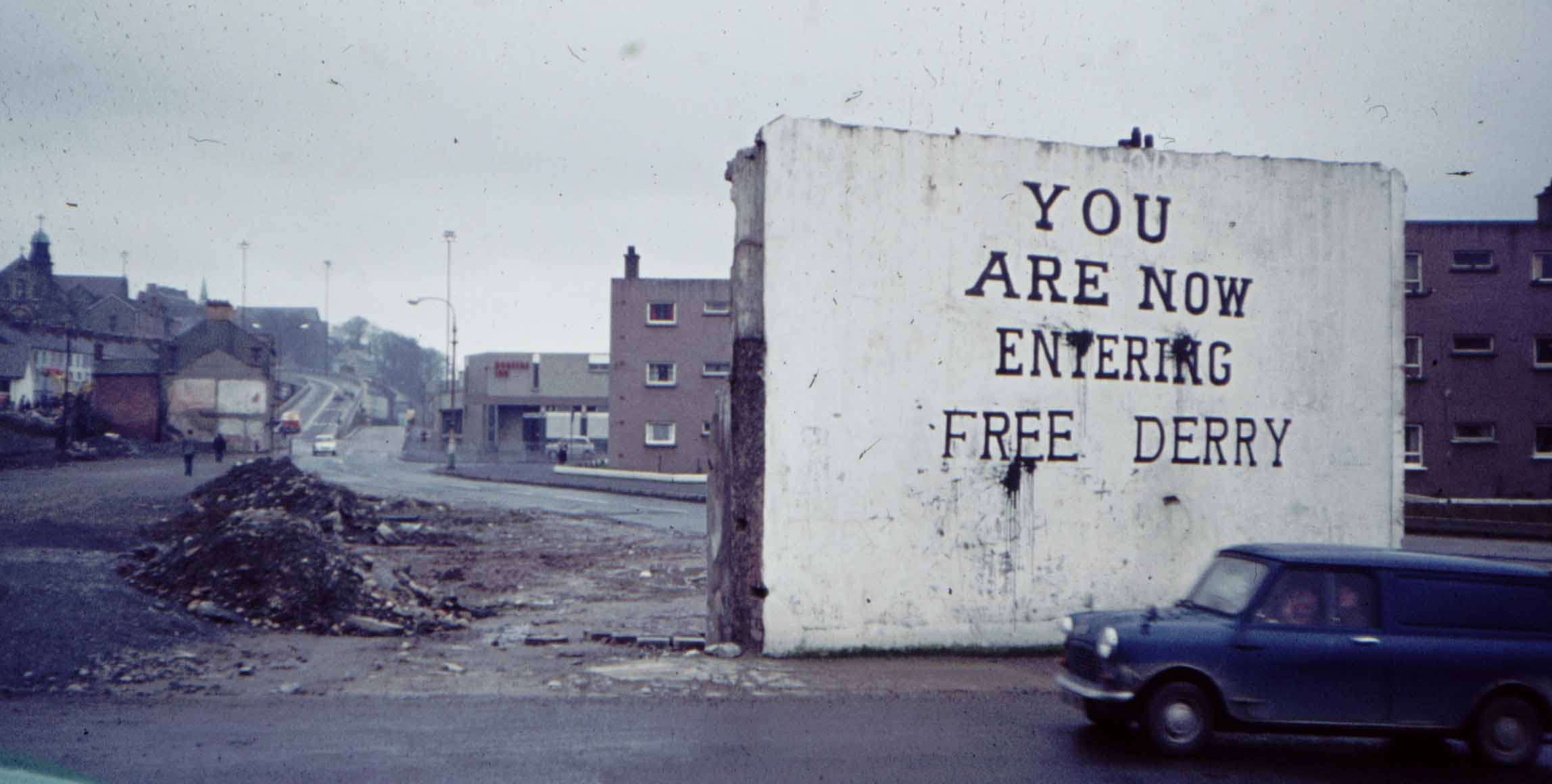

Darkness comes early in Derry in January and as night fell the RUC attacked shoppers in a city centre store and smashed glass counters. Later that night the RUC Reserve invaded the Bogside, a nationalist part of town… They turned on people in the streets, throwing stones and attacking buildings, including the new offices of the Credit Union. That night ‘Free Derry’ was born. The words ‘You are now entering Free Derry’ appeared on Sunday, 5 January on the gable of a house in St Columb’s Wells. The words presaged the ‘no-go’ area that the Bogside was to become on 12 August. Though the house has disappeared the gabel-end stands free, a permanent symbol of defiance.

O’Neill made a blustering attempt to put all the blame on the young marchers but journalists in the posh papers and television pictures told another story. Up till that moment the RUC as a force had been again getting a sort of acceptance by the nationalist community but now they were totally execrated. The ferocity of some of their members that night in Derry had a kind of millennial temper as though they instinctively believed that this was the end or the beginning of something in the North. S. M. (p. 92)

An innate predisposition to forgetfulness. This seems to be my parents’ virtue, especially my mother’s. This is how she removes pain.

An innate predisposition to confuse the faults of her two daughters, so she didn’t have to scold the daughter that seemed more fragile.

I, rather than not going to school, went and got 3s, since I got them whether I studied or not. No one had ever understood my real problem: the ability to dream. I believe I have lived incredible, countless adventures and for this sometimes I confuse my dreams, because I have formed, in blinks of an eye, many personalities inside.

The spring came, surely the most eventful in the history of Northern Ireland.

Since Fenian times or even earlier the ‘armed struggle’ had been part of Republican mythology as the only reliable means of defeating the British. Now smarting from the failure of Operation Harvest they began to regroup and the month of December 1969 was to see a split in their ranks into the ‘Official’ IRA, known as ‘Stickies’, and the more militant, rather right-wing group called ‘Provisonal’, who remained obstinately abstentionist in opposition to the Officials who had had some aspirations to constitutional, if rather radical, politics. The Official IRA declared a ceasefire in May 1970 after a number of atrocities that they claimed weakened their cause but the Provos, as they soon came to be called, continued their campaign until 1994. The reinvigorated IRA was a product of the end of the year 1969. S. M. (p. 93)

In the end they always believed that I was the strongest; the one that set out defending the other two women from an apparently troublesome father… a father that simply could not express emotions any more – they were stuck, choked together with his illness but always there, in the vicinity.

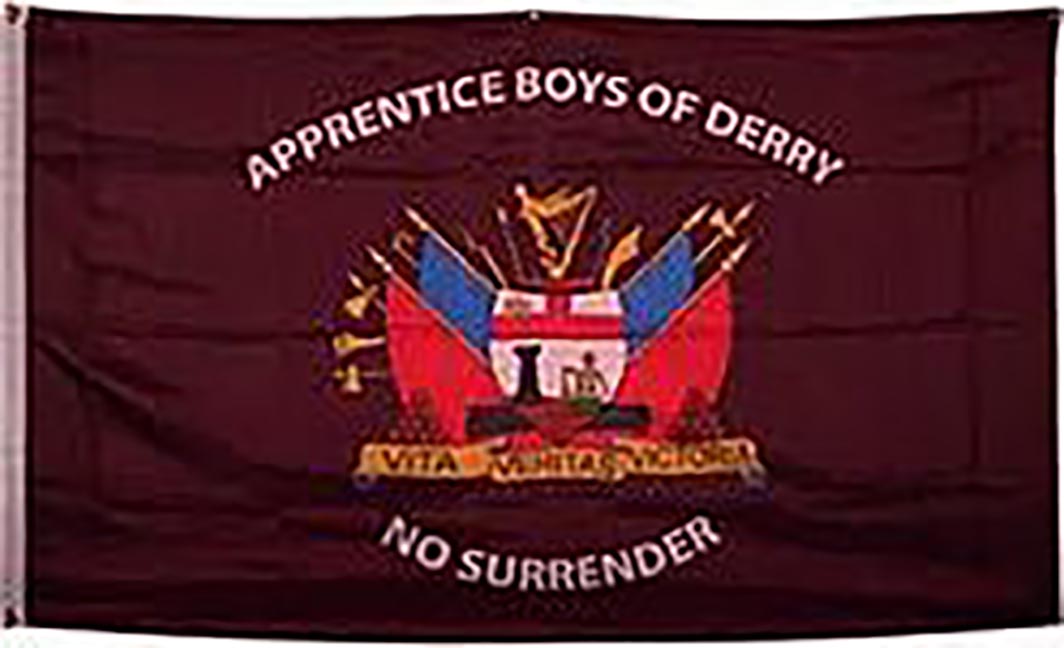

July came with the chief Orange celebration of the ‘glorious, pious and immortal memory’ of William of Orange… on the ‘Twelfth’…

There was trouble in Dungiven and Derry but what people dreaded was the Apprentice Boys of Derry’s celebration of the end of the famous siege in 1689. The society has been founded in 1814 in token to the thirteen London apprentices who had symbolically shut the Ferryquay gate against the Jacobite troops of Lord Antrim in December 1688. Their day was the other ‘Twelfth’, 12 August, and the ritual included a circuit of the carriageway on top of the city’s walls. Trouble was almost a certainty considering the temper of Derry nationalists, especially those who lived under the west wall. In the past they had greeted the marchers with black smoke from their chimneys. S. M. (p. 94)

You have no way of knowing this but I remember many “couples” discussions you had.

You were convinced that I was watching TV but instead I was listening to you. I’m very good at this!

Of course, however, from there I came up with some real films about it; other films, about you, about sexuality. But you never wanted to talk about it.

The day’s events were almost over when trouble began. It was said that some of the marchers had tossed pennies down from the walls; others claimed that nationalist youths had thrown stones at the marchers. Whatever the spark the Battle of the Bogside began not long after five o’clock on the evening of 12 August and lasted until about the same time on fourteenth. During those forty-eight hours much had happened elsewhere. S. M. (p. 95)

Bogside, Derry, 2013.

The call by the DCDA to nationalists about the North to show support to Derry resistance had direct effects to Belfast. It was interpreted incorrectly by Unionists as a general call for insurrection.

All Catholics were the enemy and the actions of hooligans on both sides made the old enmity lethal. S. M. (p. 96)

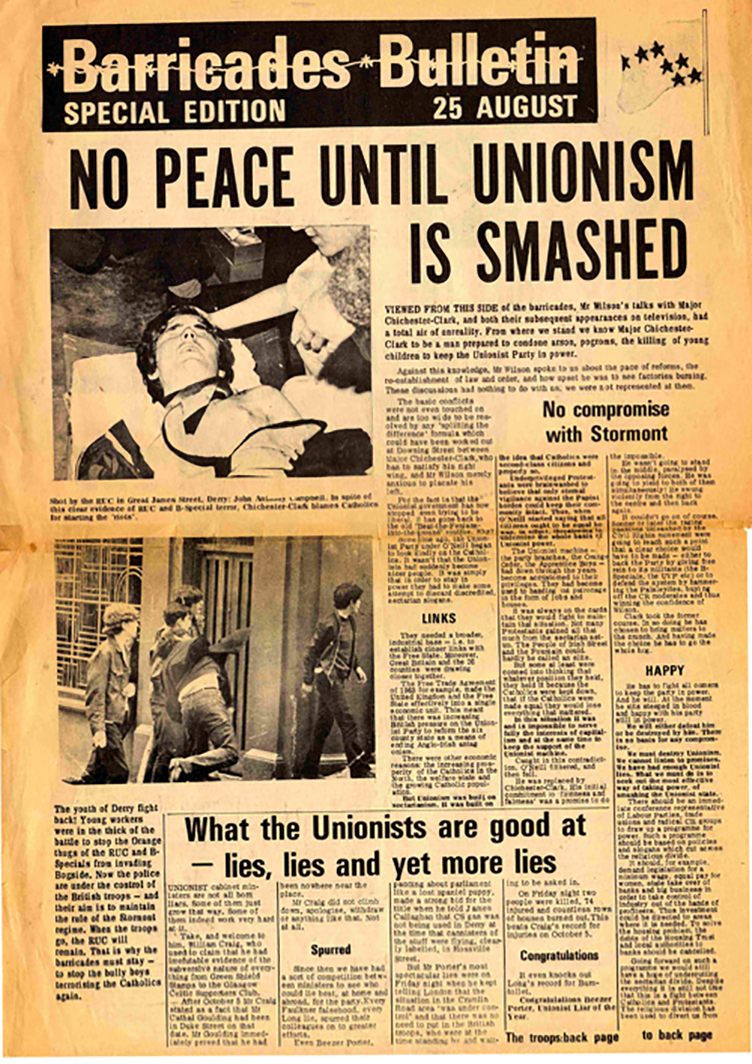

“Barricades Bulletin”, 25 August 1969

In Derry many very young people were involved in the Bogside battle… S. M. (p. 96)

Clive Limpkin, Ulster’s Boy Petrol Bomber.

One of the most famous image of The Battle of The Bogside.

How many times did you run away when faced with the evidence of my femininity? Why didn’t you accept it? Why did you run away like that? Did this happen only with me? I perhaps was trying to throw reality in your face. You, hiding behind the possible paternal reactions and also weaknesses of heart, you made it so for years I lived it like you did.

What a liberation to know that it’s no longer like that.

PIRA, as the Provisonals now called themselves… had agreed to begin the long war that would surely lead to the desired reunification of the country.

The government officials, the army, the RUC, and the Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR) that replaced the B-specials on 1 April 1970, all seemed to the IRA to be the means of perpetuating the partition of the country and so were regarded as ‘legitimate targets’. No one seemed to understand the determination of IRA recruits or their courage.

Their support by their communities was based on the belief that they were the only defence against the UVF and, from August 1971, the Ulster Defence Association (UDA), the RUC, and the BA (British army), as the once welcome soldiers came to be called. The piece lines in Belfast were not simple marks on the link roads that led, say, from the Falls to the Shankill, but high wire fences set in concrete.

The first action by the security forces that increased enrolment in the PIRA was the illegal, no-warning curfew imposed on the Lower Falls on 3 July 1970. It lasted thirty-five hours, during which there was no means of obtaining food and 20,000 people, including children, were kept confined while 5,000 homes were searched with much damage to property. S. M. (pp. 98-99)

Believing I was strong, they never saw my real weakness that was there, between that smell of anaesthetic, those scars that my sweatiest nightmares gave me.

Rioting and bombing became a part of the daily life in parts of Belfast and Derry… S. M. (p. 100)

A Piece Line in Belfast.

Science, science, science that invaded my ears. Blood and disease that seemed to absorb me. So I pushed myself towards the spirit, embracing all that I believed to be worthy of my attention. Sometimes I even invoked death, to free myself. I was a slave of my imagination, of my dreams – there were too many of them and they were too strong.

Slowly I tried to live out all of them.

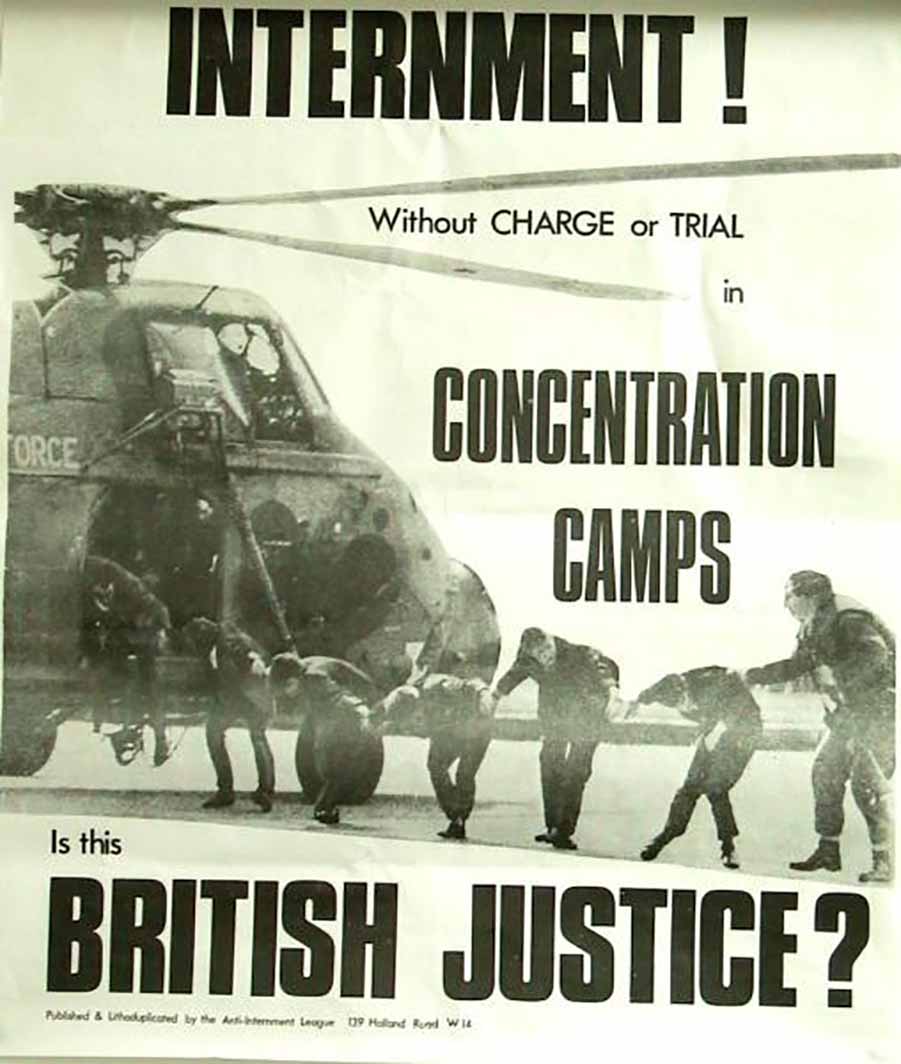

Now Faulkner decided to hold another recruiting drive for the IRA. Obviously he had no such idea but his action in introducing internment without trial had precisely that effect.

… of the 343 internees who were brutally lifted and badly treated at 4am on 9 August 1971, there were very few Protestants…

Fewer than eighty of those interned in Crumlin Road jail and the Maidstone, a converted troopship, were PIRA members and none significant. Those retained were subject to the techniquest of modern interrogation: torture, sleep deprivation, white noise, hooding and starvation.

Many young nationalists rushed to join the PIRA, assenting for better or worse to the presence of paramilitaries in their communities.

Internment was to lead to one of the blankest days in the history of the Troubles. S. M. (p. 101-102)

My body spoke to me in a dream.

For some time, in fact, I was a bit too tired, exhausted, weakened.

I dreamed of “giving up”. I decided that all that noise, the people, the rules had deeply tired me out; I wanted to make them all inactive. I lay down beneath a bench to switch everything off.

Immediately after – awake in the dream – I witnessed a complete surgical opening of my chest. Doctors and nurses; the lights of the operating room. I saw everything but I didn’t feel pain. Afterwards, the doctors were amazed at how I managed to see everything and not feel anything. There was no need for an anaesthetic.

Another anti-internment march was fixed for the following Sunday week, 30 January. A few stones were thrown that day and then, in spite of advice from the local head of the RUC, District Inspector Frank Lagan, the members of the Parachute Regiment and the Green Howards shot twenty-six unarmed people, thirteen of whom died in the streets and a fourtheen later of his wounds. S. M. (p. 103)

[In 2014 there was a YouTube video placed here, no longer available and named Full unseen footage of British Para’s killing 14 men+boys 1972]

This time I damn awake.

That pulled flesh, that horizontal patient.

To see around oneself doctors, nurses, relatives.

To not be ashamed of your own body.

There is no sexuality at all. I undress easily.

I accept that I am a body and nothing else.

It’s useless to argue about this. It’s useless to wage a battle against a certain kind of doctors.

I simply created distance between us.

This time NO. The matter is serious. I’m not dreaming. You, however, all seem completely out of control.

I yelled out my rights and, alone, I took back a life that wanted to leave, by the hair.

It caused countrywide rage and grief, and led so many young people to flock to join the PIRA.

Whitelaw met members of the PIRA secretly in London during a short-lived truce in early July 1972 and after the carnage of 21 July called accurately ‘Bloody Friday’, ordered Operation Motorman which on 31 July ended the so-called ‘no-go’ areas in Derry and Belfast. S. M. (pp. 103, 106)

The body is mine. I decide and I speak only with those that show it respect.

I never would have believed I could fight so for my body.

I never would have believed I loved myself so much, I was convinced that I despised myself.

On 29 May 1972… the OIRA announced that they were calling a ceasefire because ‘The overwhelming desire of all people of the North is for an end to military action by all sides.’ The PIRA and the UDA were unmoved.

The latter numbered 40,000 members by the end of 1972 and began shows of strength with marches in combat uniform and bush hats through Belfast city centre….

In fact the UDA was a legal organisation until it was proscribed by Sir Patrick Mayhew…

They were one of the number of organisations dedicated to the preservation of the Northern Ireland state, which they obstinately called Ulster… Closely associated with the UDA were the Ulster Freedom Fighters (UFF).

The PIRA was similarly not the only active force on the Nationalist side. In 1974 some members of the OIRA formed the Irish National Liberation Army (INLA). It had left-wing tendencies and developed a reputation for greater ruthlessness than the PIRA. The killing on 30 March 1979 of Airey Neave, the close associate of the new prime minister, Margaret Thatcher, and their spokeman on Northern Ireland, by a car bomb… got them world attention.

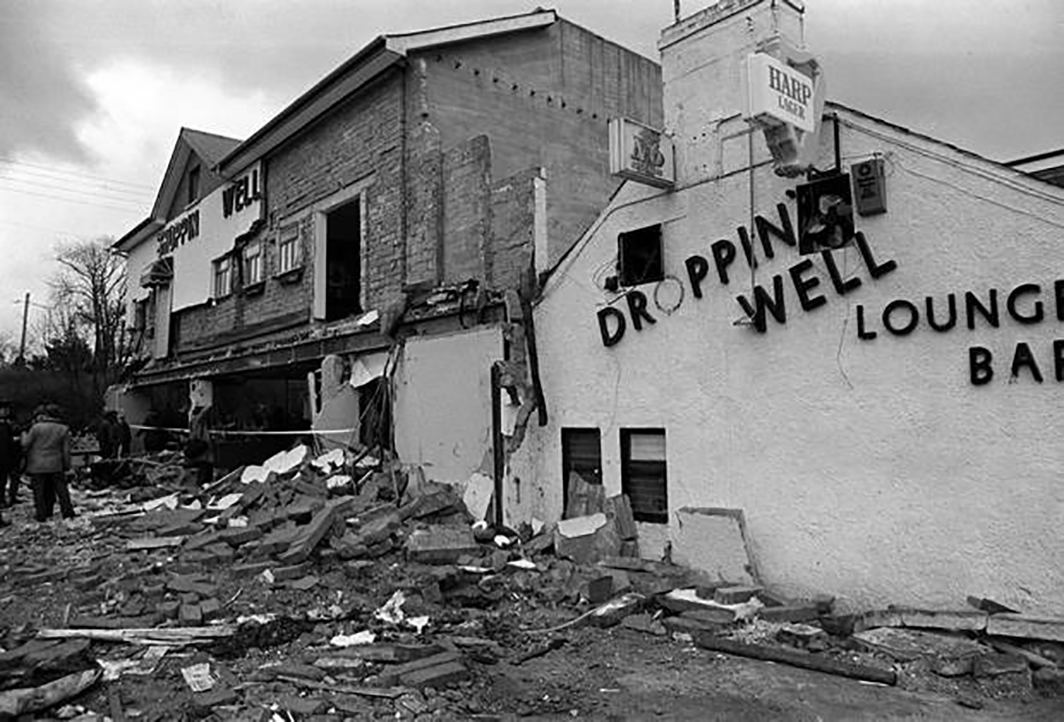

On 6 December 1982 their no-warning bomb at a pub-disco in Ballykelly, County Derry, called the Droppin’ Well, killed seventeen people (eleven soldiers and six civilians). S. M. (p. 107)

When you become so respectful and symbiotic with your own body, pain is no longer frightening, if you need healing.

Never again, though: people that discuss my flesh in front of me without thinking about me.

Never again: fingers pointing as I sit in a corner, confused, with a headache, tortured by constant hands that palpate, mechanical instruments that press, bruises that re-emerge blinded by so much insensitivity.

Never again: the looks at a screen, trying to understand the inside of me, when I already have, by myself, first, long before you.

One last IRA atrocity should be mentioned: on 15 August 1998, four months after the Good Friday Agreement, the Real IRA, a dissident group that did not accept the terms of the agreement, exploded a 500lb bomb in Lower Main Street, Omagh. It killed neneteen adults and nine children (a twenty-ninth victim died on 5 September). Though the Real IRA, accepting responsibility, said that all military operations were being suspended it was believed that some of its members joined the Continuity IRA, the only Republican paramilitary group not on ceasefire.

Loyalist paramilitaries were not idle… As with the Republican groups the campaign to save Ulster and prevent a united Ireland was kept to a general, almost quotidation, level of violence with occasional spectacular atrocities. The killing of fifteen people by the UVF in McGurk’s bar in Belfast on 4 December 1971 marked the culmination of a bleak year. S. M. (p. 109)

Yes, the body cries, it cries blood.

My skin is grey. My smile struggles and my face hides my thoughts even less than before.

Insensitivity, uselessness, superficiality is everywhere. I already knew that, but now the last mask is no longer there, and it hurts me greatly to see the world for what it is.

The total number of fatalities in 1975 was 247, of which 217 were civilians… On Saturday, 5 April a bomb thrown into McLaughlin’s bar in north Belfast killed two Catholics; it was answered by a bomb three hours later in Shankill Road pub that killed five Protestants.

The killing continued, extended by the PIRA to England. The ‘Birmingham Six’ case involved six men sentenced to life for their alleged responsibility for the bombing of two pubs in Birmingham on 21 November 1974 in which twenty-one people died. They were freed in 1991 after seventeen years in prison after the longest campaign against a miscarriage of justice in legal history.

The release of the ‘Guildford Four’, who had also been sentenced to life for the pub bombs in Guildford and Woolwich on 5 October and 7 November 1974 on the basis of confessions later retracted, gave greater impetus to the Birmingham Six agitation. S. M. (pp. 110-111)

The real operating room. The lights, the screens. Those that try to comfort me. To do that, they always ask the same questions.

Three anaesthetics in total. Operations of various durations in which, three thrice in an incredibly short amount of time, I went through the four phases of Sedation, Hypnosis, Analgesia, Complete Relaxation.

General anaesthesia is a condition of reversible coma, induced artificially.

I hardly remember the first awakening; I remember more the panic of the staff’s entrance and the unacceptable lack of understanding.

The second and third I remember very well, in the Awakening Room.

The third time I have a good memory also of the preparation, of the man that I had next to me, of the discussions of my anaesthesiologist with a nurse.

Now I look at needles that go into my veins with a certain tranquillity and, perhaps, curiosity.

I actually started talking about the grey Milan weather in the operating room and, as they immobilized my arms and legs, I even indulged in comparing the aesthetic of the various operating rooms I had been in. Then there was no need to make me sniff any calming agent.

I am perfectly calm.

I know my body.

I know it will rebuild itself.

I’ve seen it heal itself like no one else could.

I was shocked and amazed by such talent.

The PIRA continued to believe that it was a useful and, of course, legitimate part of campaign. One of their more notorious ‘spectaculars’ was the attempt to kill Margaret Thatcher, then prime minister, and her cabinet at 2.45am on 12 October 1984 in the Grand Hotel, Brighton, during the Conservative annual conference.

The return of a forth Conservative government on Friday, 10 April 1992 was commented upon by the PIRA with a 1000lb Semite bomb at the Baltic Exchange in the City of London that killed three people, injured ninety-one, and caused 700 million pounds worth of damage; and the 1994 PIRA ceasefire was ended abruptly at 7.01pm on 9 February 1996, with a bomb at Canary Wharf which killed two people, injured more than a hundred, and did more than 85 million pounds damage, slowing the peace process and causing Sinn Féin to express surprise.

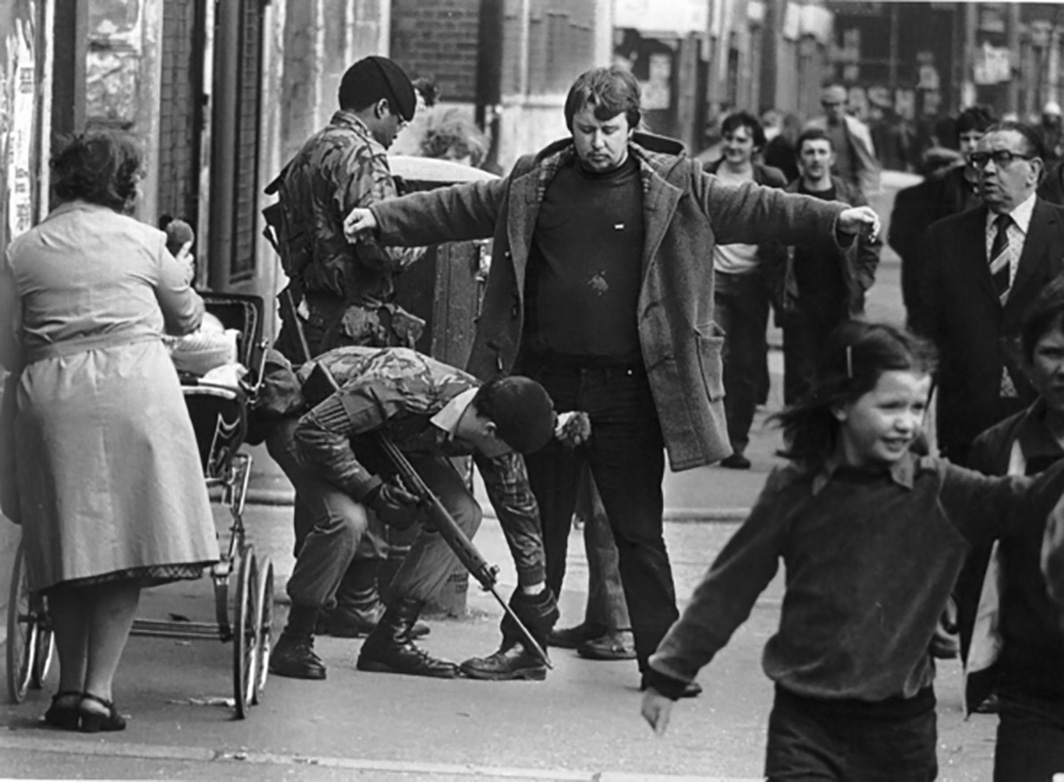

Security gates became a feature of urban life as also were often unpleasant body searches.

Army and police checkpoints were imposed without warning… S. M. (pp. 110-112)

© Mr Breandan Murphy

Especially having escaped from the greatest danger.

Especially, thanks to that danger, after having had delicious banquets with a present without a future.

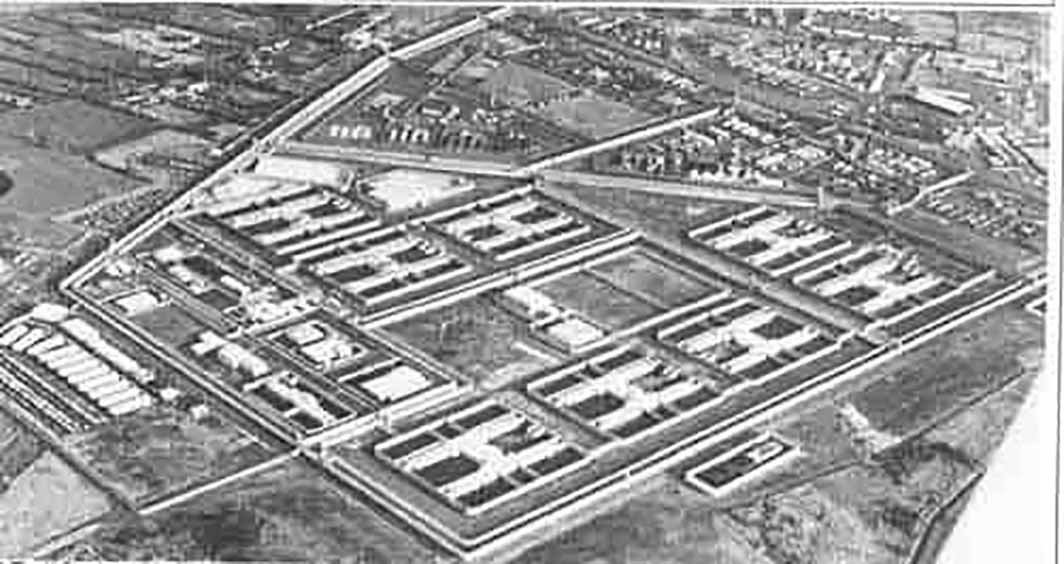

‘Criminalisation’ meant that prisoners could not longer wear their own clothers or have the privileges granted by Whitelaw. They were housed in the new Maze prison near Lisburn, County Antrim, that had blocked buildings in the shape of the letter H. (p. 116)

Protests began almost immediately: prisoners draped themselves in blankets and began the ‘dirty protest’ that meant no use of toilet facilities.

Their cells, which they refused to leave, were often smeared with excrement. (p.116)

First TV footage of the Dirty Protest in the Maze prison, made by Robin Denselow for BBC. Video still.

This frame is one of the most known one. Was also used by Richard Hamilton, in its The Citizen (1982) at the Tate Collection and in the installation Liquid Diet by Mike Kelley (1989/2006).

First TV pictures of the ‘dirty protest’ in the Maze prison by Robin Denselow.

True fear leads to endless nausea.

True fear leads to endless freedom.

Tatcher, already demonstrating the right-wing inflexibility that led to her being called the ‘Iron Lady’, was determined to increase security, having no obvious desire to find a political solution.

Atkins’ term of office produced one of the greatest crises in the whole of the current troubles. The one traditional weapon that the PIRA prisoners had not yet used officially in their struggle against ‘criminalisation’ was the hunger strike. Seven prisoners, dismayed at the lack of success of the ‘blanket’ and ‘dirty’ protests, began strike on 27 October 1980. It lasted until 18 December when Atkins seemed to have offered some concessions of clothing. The offer was not what the prisoners took it to be and Bobby Sands, OC of theH-blocks, began another strike ‘to the death’ on 1 March 1981.

He was to be joined by another striker each week. His election in Fermanagh-South Tyrone three weeks before his death, defeating Harry West, the former leader of the Unionist Party, by 1,4446 votes, gave a great boost to the campaign. His funeral on 7 May was attended by 70,000 mourners and… there was serious rioting in Belfast and Derry.

All during the summer of 1981 deaths in the H-blocks blighted life in the North. The sequential nature of the protest meant that, in spite of protests and recommendations by Dublin to other governments to intervene, the ghastly regularity continued.

The campaign had led to the deaths of sixty-one people, including thirty members of security forces. Three days later James Prior, the new Secretary of State, announced that prisoners could now wear their own clothing. S. M. (pp. 117-118)

When you are faced with the colour of your own blood and you caress your scars like children, time no longer has any meaning.

Though Thatcher’s hard line on the strikes seemed to have prevailed there was no decrease in violence. The long-drawn-out sequence of slow dying, death, emotional funerals and concomitant rioting made it the most depressing time of the Troubles. Yet for a number of reasons it marked a turning point in the process. Catholics and Protestants became even more polarised. S. M. (p. 119)

When you have a second chance, you discover that time is infinite.