The Noise of the Flag | Part I

Fully to understand the North requires some knowledge of the ancient province of Ulster and its seventeenth-century plantations. The Irish as a nation – Ulster being no exception – are accused of being obsessed by history. The truth is that the Irish know very little history but are imbued from childhood with much visceral propaganda. S. M. (p. 146)

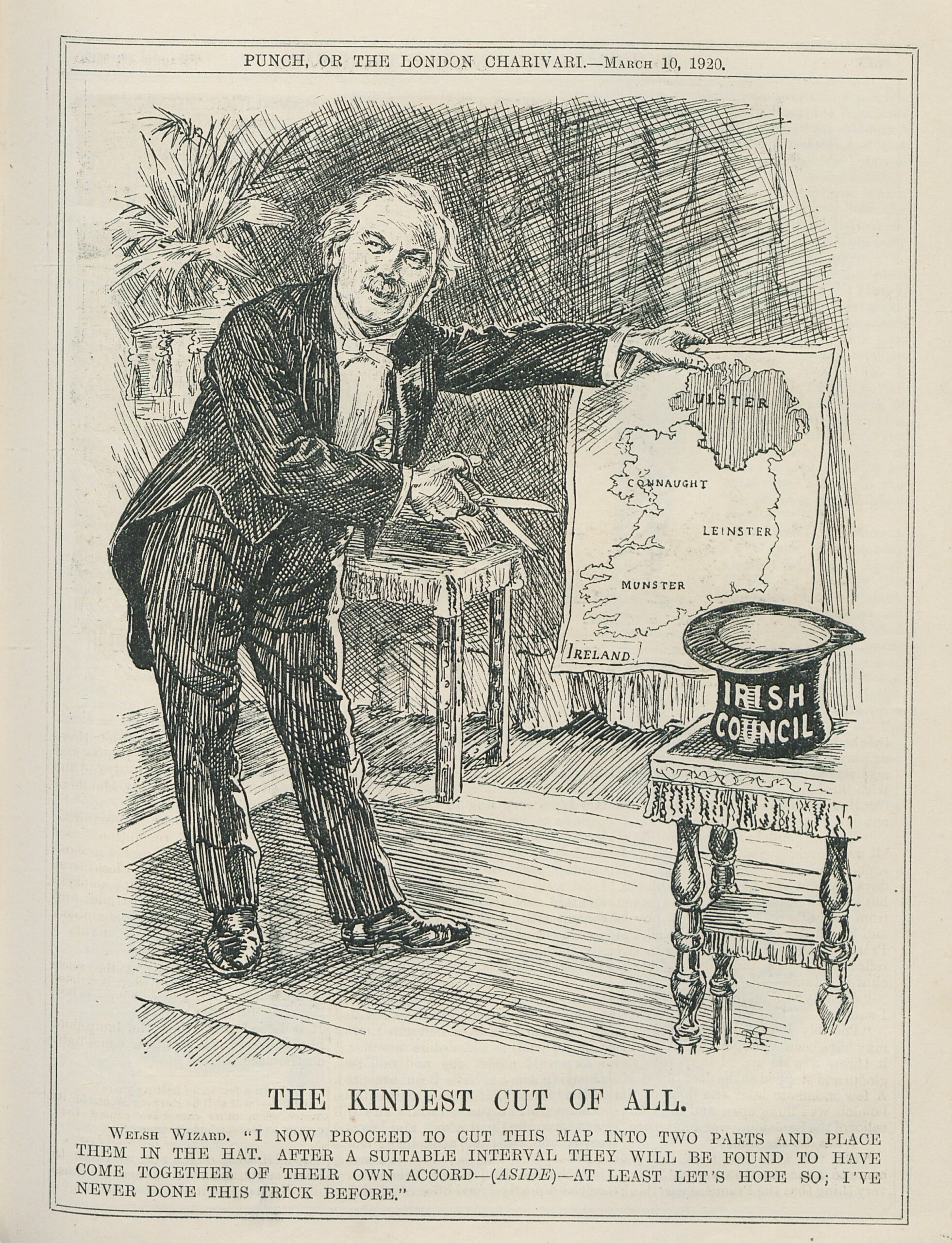

THE KINDEST CUT OF ALL

Welsh Wizard. “I know proceed to cut this map into two parts and place them in the hat. After a suitable interval they will be found to come together of their own accord – at least let’s hope so; I’ve never done this trick before.”

“Punch” magazine. Cartoon by Bernard Partridge, March 10, 1920.

We proceed, waiting patiently, draining.

We resist the traps of fear despite the cement, the mosquitos, the criminals around the corner.

We accept our bodies with stoic endurance of the pain and yet, in our thoughts, we still believe we are not able.

We romanticize our angels and saviours to whom, instinctively, one would give his or her own life – soul and body – and TOTAL loyalty.

We are privileged with awareness and those who watch our red appendages know it deep down. Those who pity my youth, instead, don’t know that I will not waste any more time.

But Belfast, as ever, bore the brunt. It was the scene of recurring sectarian conflict over the next two years (1920-1922). In that time 453 people were killed; of these thirty-six were members of the security forces and the rest civilians, 257 Catholics and 159 Protestants. More than 10.000 Catholics were driven from their jobs and 23.000 (a quarter of the total number of the city) were forced to flee their homes.

By the end of 1921, the total number of killings was 109.

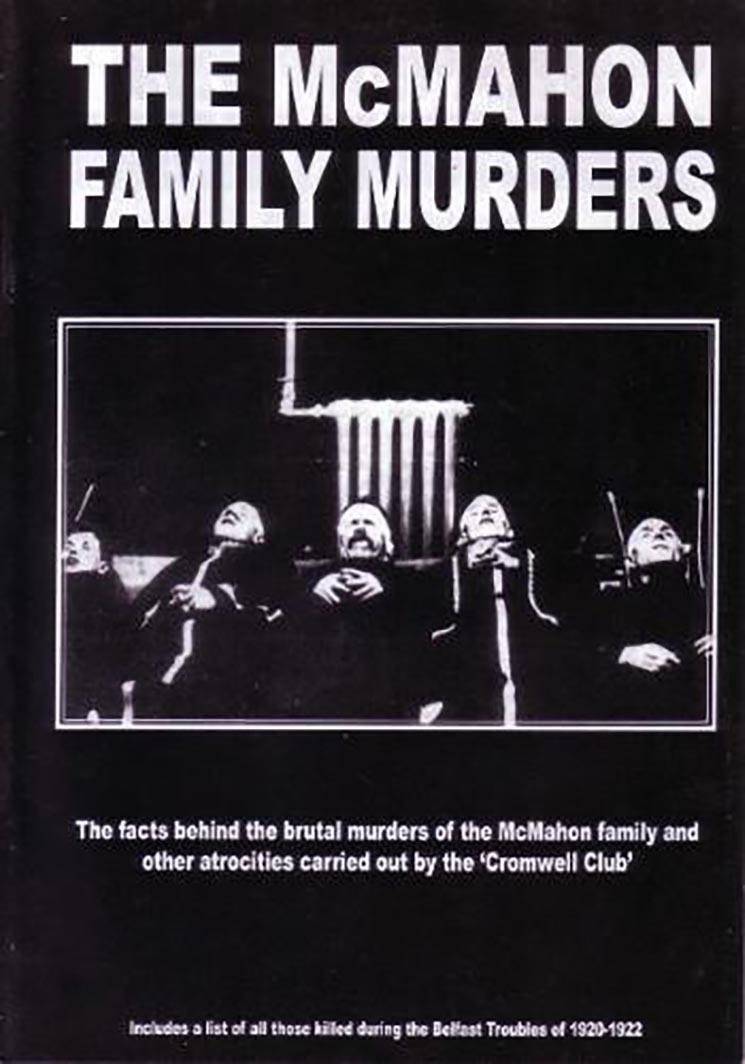

It was the killing of the McMahon family on 24 March 1922, however, that shocked even those most hardened to the cruelty of the times. Sean McMahon (pp. 24, 29)

On the floor, dark marble streaked with white and beige, in the lamplight of the living room, I was intent on playing, probably with a toy car. For a long time I preferred games for boys, like marbles, to be raced along paths created on carpets of childhood winters; games to play in company.

The late afternoon warmness of that living room still melts my heart today; a sign that my childhood was filled with warmth.

As I watched the toy car move, fuelled by my imagination, the phone rang. My mother’s voice became icy cold and caused a shiver to run down my spine.

This was the first time that death entered my life. This is one of my first memories. My maternal grandfather had died. He had been dying for years. I remember that I took care of him, rocking on a small teal chair, when we went to visit him at my mother’s house in her hometown. I was convinced that, being near him, I could speak to him. I wasn’t afraid at all.

Still today, when I have the flu, I prefer to eat mashed banana with a bit of sugar and some freshly squeezed orange juice. It’s not that it brings me back to my childhood, but it reunites me with my grandfather who, paralyzed by a stroke, could not eat solid foods.

The Special Powers Act, as it was usually known, was kept on the statute book long after the threat of civil war was past and was made permanent in 1933. It was regarded with envy by the apartheid leaders in South Africa.

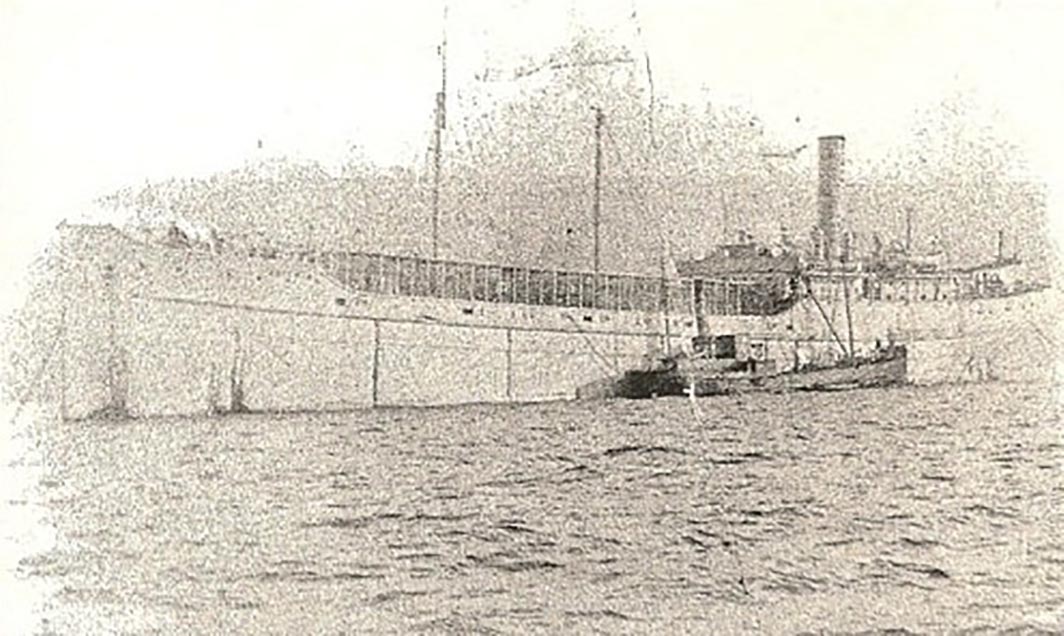

The most dramatic use of the special powers occurred with the incarceration of 300 IRA suspects on the prison ship Argenta in 1922…

The Argenta was a wooden ship of American manufacture …

The internees were kept in cages forty feet by twenty feet by only eight feet high….

Tuberculosis, pneumonia and other infectious diseases…

The internees were mainly middle class professionals who kept up their spirits by publishing the Argenta Bulletin, a samizdat, handwritten production wryly describing their imprisonment.

It was not until 1926 that all the internees were released and the hulk scuttled. S. M. (pp. 33, 35)

The Argenta, moored in Larne Laugh to hold internees, 1922.

Not long ago, in the same room, I beheld another dying man. My uncle, my favourite uncle, who I always saw as tall, strong, eternal, with his moustache, his nobility, his cigar, his everlasting light-heartedness. He enjoyed life, though didn’t move much.

For my part I wanted, at a distance, to understand why I was always so attached to him, so I studied my family history. Still today I am the keeper of his photographs. I created a memory of my uncle for myself, as if I had seen him be born, grow and then leave us.

The last memories I have of him are his heartrending cry of pain, his thinness, his attempt to speak to me. Fortunately, some time before, I had broken the reins that had always harnessed my family with a strange fear of showing affection, and in the hospital I took his face in my hands, I caressed him, I got close and our breathing merged, I kissed him and I told him that I loved him. I love him. The goodbye was sweet, as sweet as his voice and as his life, where I saw the keys to serenity.

In practice there was little territorial segregation. In most towns members of the tribes were next door neighbours. For historical reasons the poorer areas tended to be Catholic though there were poor Protestants as well. Middle class areas were what in the Gaeltacht – with, of course, a linguistic and not a political sense – would be called breac (‘speckled’). Catholics and Protestants lived in formal amity. There was no colour bar nor were physical tribal characteristics all that reliable, in spite of boasts by both sides. Orange, crimson and black marches were seasonal events and where it was safe there were also green ones, notably St Patrick’s Day and on 15 August, the feast of the Assumption. Outside of Belfast there was general support of local soccer teams, golf clubes had mixed membership, and the dole queues were non-sectarian. S. M. (pp. 38, 45)

I remember my father’s “first” heart attack through an image: a deer, fixed on eating the leaves of a tree, surrounded by greenery. It is the front of a postcard sent from Switzerland, dated the 1st of December 1983 and addressed to me… I was only 6 years old.

Recently I found that postcard again.

Things that are kept over the years, brought from house to house, left at the bottom of a drawer and then, suddenly, found again, always have the taste of rediscovery and omens.

Certain far-off documents are often found again in moments of tidying up, ordering. True order, which makes you dig through, sort out and throw away whatever has become too dusty, in the bottom of the drawer or in the darkness of a cellar, is usually driven by a need for renewal, in one’s surroundings and in one’s soul.

Renewal, by force of circumstances, must also review history.

There came a time in 1932 during a period of high unemployment (…) led to united public disorder with both sides briefly joining forces to demonstrate against the system.

It began on the first Monday of that month [October] and lasted for about ten days. There were protest marches, torch-lit processions and rioting in both Catholic and Protestant areas when, on 11 October, the RUC tried to ban a march.

Unsophisticated Protestants found themselves afflicted again with atavistic fears and it was comparatively easy to revive militancy. S. M. (pp. 50-51)

That postcard, with various writings on the back.

My mother, whose handwriting I recognize, could only write the date, evidently not being able to resist, even in this case, affixing a chronological mark, some order, a fact.

Now, she has this date confused, master as she is of the removal of pain.

I, however, have the proof and with it a picture of what I was like; I was 6 years old, and I remember that postcard, that deer.

They were in Switzerland, a place I’ve never returned to… because I’ve already been, with my childlike imagination, projecting great fragility on that greenery and on that poor deer, the same that can be read in the rest of the handwriting. The address (mine) – my mother wants to give me independence already at age 6? – and the sentence “Many kisses / Mum / Aunt Gina / Dad” is absurd, to say the least. It seems to be written by another child. Myself?

In those weeks had they simply gone on holiday?

Perhaps I perceived it almost in this way: they had decided to take a holiday from us.

The Westmister attitude had, since 1920, been, and would continue to be until the end of the 1960s, rather like that of the headmaster and staff of an English public school. They left matters of discipline to the senior prefects who would have the power to keep junior common room under control.

…new parliament buildings at Stormont… on 16 November 1932. S. M. (pp. 53, 55)

The next memory I have, though, is a nightmare.

A nearly naked body, wheezing, aching, with deep and long scars.

That body calls to me.

The view is obscured by the vision of torn flesh and that pervading smell of disinfectant.

A nauseating smell.

That body is my father.

He calls to me because he wants affection and he wants to comfort me.

Did I give him affection? I have no idea.

From that point, my dreams were never the same again.

My relationship with the body was never the same again.

Display of affection was never the same again.

Fear of disease had completely replaced the fear of death.

The outbreak of war on Sunday, 3 September 1939 was used by several interested parties in Ireland as an opportunity for advantage.

The IRA declared war on Britain after the four-day period and between then and July there were 127 explosions, seven deaths and 200 serious injuries. As with later campaigns the only real victims were the exiled Irish who bore the burnt of complaint from their neighbours.

The ports became less significant with the entry of America into the war after 7 December 1941, when Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. The port of Derry became central to the war effort… On 30 June 1941… nearly 400 American ‘technicians’ arrived to prepare for the US forces that were certainly going to come and whose presence on Irish soil would be predictably objected to by Valera as ‘occupation’. The built a submarine school…., accommodation camps and new quayes.

By May 1942 there were 37,000 of these generous exotics and the terminally depressed town became for a few years a lesser Babylon on the Foyle. S. M. (pp. 58, 61, 64)

Many years ago, as a teenager, I think, in the living room of our house in the mountains – the house of redemption – I remember my uncle and my father laughing, smoking and playing cards. My uncle came often, to gather mushrooms.

It’s the only memory I have of a father that enjoys life.

In spite of the politician’s self-reassurance… that the north would never be a target for aerial bombardment, Belfast came face with the terrors of modern warfare on four spring night in 1941.

The raid on the night of 7-8 April 1941 that badly damaged part of Harland & Wolff and the docks, and killed thirteen people, was just a taster. Easter Tuesday, 15 April, brought 180 German bombers that devastated the civilian areas of the lower Shankill and Antrim Roads. The destruction of the main telephone exchange cut off communications with the anti-craft placements and with Britain.

Nearly 800 people died, and since the city mortuaries could not house them, the Falls Road swimming baths were drained and 150 bodies were laid out there. Two hundred and fifty were taken to St George’s Market and the unclaimed bodies were buried in a mass grave on the following Monday. S. M. (pp. 64-65)

Harland & Wolff cranes seen from East Belfast, 2014.

Once I went with my mother to do some shopping. She parked in front of an electronics shop and she asked me if I wanted to go with her or wait for her in the car. I wanted to read some comic, which I only remember as having green characters, perhaps aliens? So I chose to stay and wait for her. I finished the comic, I read it again… I read it again. In the end, the wait seeming like an eternity, I deduced that my mother would never come back and, with seraphic calm, I got out of the car and approached another nearby car where another mum and a teenage son were getting in. I started to tell them that my mother had died. I wanted to be adopted. My mother returned.

For a long time, whenever a member of my family was absent, he or she was dead to me, and I managed to remain calm.

Electronics shop, Rome, 2014 (closed for years).

One summer day, my sister left. I asked where she was going and my parents told me she had gone to buy milk.

I hope this habit of lying to children has passed…

After one day, I finally took the trouble of announcing my sister’s death. At that point they told the truth: she had gone to a friend’s house by the sea. They hadn’t told me because they thought I would want to go, too, but my sister didn’t want me there. I remember the time I spent on the ground very well, in front of the door, waiting for her.

It was such a deliberately partial allocation in the village of Caledon in County Tyrone that led to the first civil rights march, the initial step that led to the domino sequence that brought the conflagration of the ‘Troubles’ and the fall of Stormont. S. M. (p. 72)

Constantly dreaming, I bumped into everything. In London, at the age of 9, stuck in my dreams or attracted by some real punk (it was 1986), I bumped into poles and mailboxes all the time.

That was why everyone always believed that I was absent-minded… they never understood that I always observed everything attentively and that I remember everything. The best part is that certain memories have truly been removed from others. This creates infinite pain for me because, in this way, there is no respect for life, for those who have passed through it, for all its protagonists. It’s not fair.

And many were hardly aware of the cessation when the IRA called upon its members to dump arms on 26 February 1962. S. M. (p. 75)

IRA Volunteers, pictured around the time of the Border Campaign

(12th December 1956 – 26th February 1962)

The decade of the 1960s was different from that of the 1920s and certainly the 1930s. Because of the safety net of Welfare State life was easier. The 1947 Education Act, which provided generous grants for those who wished to attend universities and polytechnics, had produced a generation of young graduates… John Hume and Bernadette Devlin were typical of a new breed of nationalist who understood what was happening in the North and anxious, if in different ways, to change things for the better. They were aware too of radical movements elsewhere, in the southern states of America, in South Africa where the remote beginnings of the end of apartheid were just visible and, towards the end of the decade, in Prague. S. M. (p. 81)

John Hume

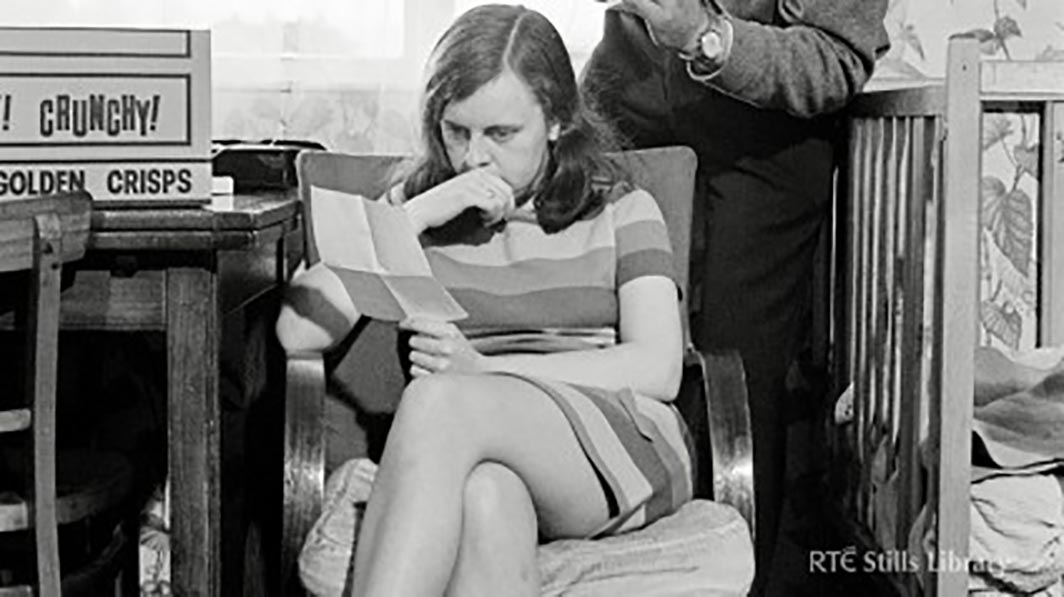

Bernadette Devlin

O’Neill’s gestures to Catholics, visiting Catholic schools, shaking hands with priests, offering sympathy to Cardinal William Conway when John XXIII died were looked at with mild interest by Catholics but with growing suspicion by grassroots Protestants.

They had found a new champion in the Rev Dr. Ian Richard Kyle Paisley. Ordained by his Baptist father in 1946 he founded his own denomination, the Free Presbyterian Church of Ulster, in 1951.

He was tall, strong and loudly effective in rhetoric of attack, and soon saw O’Neill as the enemy of the people. S. M. (p. 82)

Ian Paisley (recently deceased, aged 88)

For a few years, now I can assert with certainty, I suffered from panic attacks, between the ages of 10 and 11. Every time I was alone, I went crazy. It all started with the massive mistake of sending me to Catechism to take First Communion, even though my parents weren’t believers… though they were married in a church… the contradictions of Italy.

For some time, I don’t remember how long, I went to Catechism once a week and on Sunday mornings, very early, I went to mass instead of watching cartoons.

As would happen to me soon after with rock stars whom I worshipped as gods, I began to believe, in a morbid way. Fortunately my Catechism teacher was not very good and I started first to doubt, then to be afraid. One day, my mother was late in picking me up.

Coming down the stairs I did not see her in her usual place. My heart started to beat faster and faster, in the confusion of other parents and other children. My head started to spin. I don’t remember anything else. My mother later told me that the Catechism teacher had had to take me home.

I don’t think I went to Catechism after that, but for years I didn’t understand if I was supposed to be a believer or not, with catastrophic consequences.

The day I managed to free myself from the obligation of making the sign of the cross when I entered a church, I felt free. Practically everyone here does it, even those who aren’t believers at all.

San Ponziano, Rome, 2014.

Paisley’s first star appearance was during the 1964 Westmister general election when during the campaign Jim Kilfedder – later Sir James – was standing in West Belfast. Paisley heard that a small Irish tricolour was displayed in the window of the Republican office in Divis Street, the link between Falls Road to the city centre. He threatened to bring enough of his followers to remove it if the authorities did not. It was removed by RUC under the problematic Flags and Emblems Act. There was some trouble with the totally Catholic inhabitants. A few nights later, on 1 October, another tricolour appeared in the office and the police used pickaxes to break the door down to remove it. The riots that followed lasted two days with stones, petrol bombs, water cannon, burning vehicles, including a bus, and sirens wailing reminding older people of the civil trouble in 1935. It was also a ‘coming attraction’ trailer for many similar confrontations with the RUC facing the nationalists as if to defend the Protestants.

Kilfedder won the election and thanked Paisley for his help. S. M. (p. 83)

For a long time, I carried on with television and bread and Nutella. They were my parents. Japanese cartoons taught me attraction towards the other, sometimes towards the frightening, eroticism, a fascination towards androgyny, a terror of catastrophes.

My television was the television of 1980s Italy, where cultural, satirical or high quality musical entertainment programs were slowly being replaced by cheap irony with ever-more-naked showgirls. Luckily there were also some thrillers and series like The Twilight Zone and Twin Peaks, although they were not approved by my mother. I was often forced to change the channel, then finishing off the story in my own mind, often making it even more disturbing.

A few of those he unofficially spoke for, probably feeling the same fear of the possible dissolution of Protestant ascendancy, exhumed the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) that was going to fight and be right in 1913.

The simplistic equation ‘Catholic: IRA supporter’ led to attacks on Catholic property…

O’Neill, hearing of the murders, declared the UVF illegal… They had their revenge with explosions in electrical sub-stations in Belfast in March, post offices and buses set on fire on the Falls Road, and the explosion at the Silent Valley reservoir cutting off a large amount of Belfast’s water supply. Ironically the IRA was blamed but the outrages had the desired effect: O’Neill resigned as leader and the North headed resolutely into its Troubles. S. M. (p. 84)

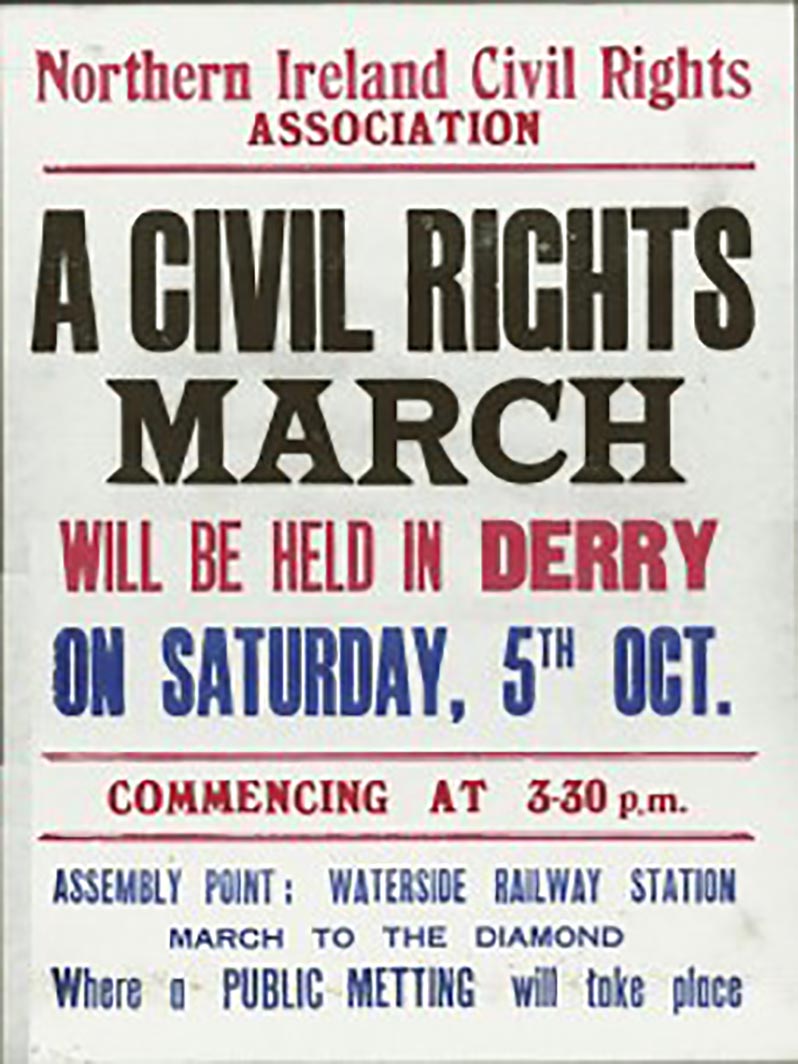

On 24 August NICRA [Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association] called Ireland’s first civil rights march from Colisland to Dungannone… all passed peacefully until the 2,500 participants reached the outskirts of Dungannon where they were met with 4000 RUC men with dogs and a makeshift barricade of ropes slung between three tenders. Paisley’s band of followers, the Ulster Protestant Volunteers (UPV), had organised a counter-demonstration and had taken over the Market Square. In the pattern of many similar confrontations the RUC stood with their backs to the Protestants and faced the NICRA marchers.

In the weeks that followed the Derry Housing Action Committee (DHAC) laid plans for the next march to be held in the Maiden City on 5 October. Craig banned the march… NICRA wanted to cancel… DHAC insisted to go ahead. S. M. (p. 87)

Video from RTÉ Archives: Derry Civil Rights Demonstration – 05/10/1968

Batons, boots and water cannon were used indiscriminately against protestors and onlookers alike, and all was recorded by television camera, especially those of RTE. People who had not attended to march but had heard the details commented, ‘So it has started, then!’ It had. The RUC’s attack was followed by two nights of rioting – and looting – setting the pattern for many similar nights and days of urban violence.