The Game Theatre of Emma Cousin at Niru Ratnam Gallery

Text written in response to the show by Emma Cousin at Niru Ratnam Gallery in London, 5 October – 27 November 2021.

Niru Ratnam Gallery. Install shot of Emma Cousin Game Face

Image courtesy of Damian Griffiths

Niru Ratnam Gallery opened last 5 October 2021 an all-paint solo show by artist Emma Cousin, featuring a new series of works showcased in the gallery’s Soho venue and its new outpost in Denman Place, London.

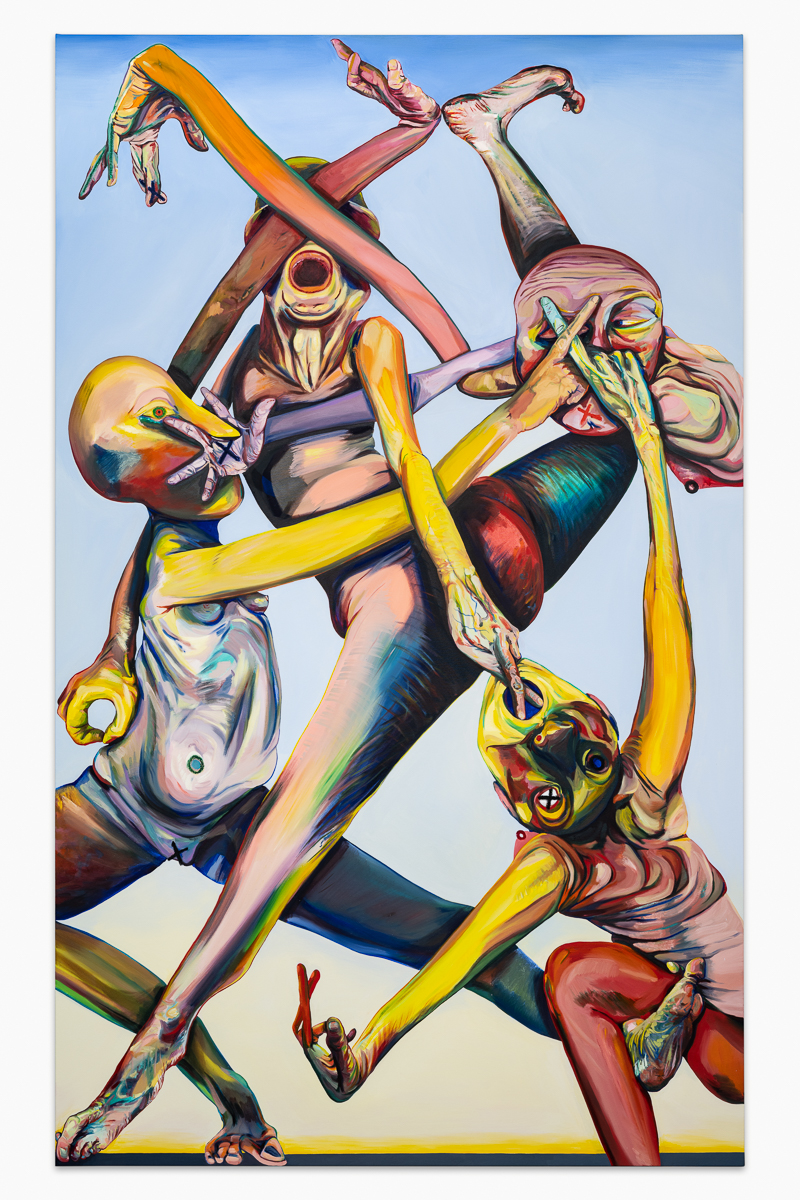

All the works presented in Game Face are entitled after some popular games that you can bet everyone from all over the world is familiar with: from hide-and-seek, Pictionary, and charade to naughty cross. Rutilant colours animate the intricate figures that populate the noisy compositions on the surface of the canvases. The gnarled, irreverent bodies inhabiting the paintings contort themselves in strange poses, as in Sardines, where three angular figures in swapping chromatics mingle, hiding their faces from the spectator. After all, sardines is nothing but the reverse game of hide-and-seek, where seekers hide with the hidden until the last player of the game.

Emma Cousin, Sardines, 2021

Oil on canvas, 80 x 100 cm

Courtesy of Niru Ratnam Gallery and the artist. Photo Damian Griffiths

If, at first sight, it is colour that stands out in these oeuvres, it nonetheless divides the scene with another element: the ubiquitous presence of faces. Emma Cousin’s canvases address the ways figures can be arranged in the space as if they were actors on a stage, thinly intermingling with the metaphor of theatre and fiction. And she does so reflecting on the meaning of certain popular expressions, such as “making a face” – as the press release gently handed over to me by Niru at his gallery in Soho suggested me – and on the role of facial expressions and body language in revealing our emotions.

Whether against an illuminated backdrop –– take a look at Monopoly ––, a bull’s-eye spotlight on a dark background –– Eye Spy –– or against a backdrop of soft, ethereal light, as in Pictionary –– where the sloping plane in the foreground is a link between the space of the stakeholder and the background of the paintings –– these bodies monopolise the observer’s attention.

In an interview with Paul Carey-Kent for Elephant magazine in 2018, shortly before Cousin’s solo show at Edel Assanti Gallery in London, the artist recounted the time spent observing and unconsciously internalising “18th century still lifes of Luis Egidio Meléndez, and the ‘body conscious’ paintings of Maria Lassnig”.[1]

One cannot help but notice how certain expedients derive from quasi-baroque-late 16th-century paintings. See, for instance, the very bold perspective view in Noughts and Cross, I would dare say reminiscent of some 16th-century altarpieces. Look at its bottom left, where the feet of the nervous standing figures rebel against the frame. The composition almost echoes the triangulations of Caravaggio’s mise-en-scenes harnessed in complex articulations of bodies (e.g. see the Crucifixion of St. Peter in Rome Santa Maria del Popolo Church). A certain “proximity to the obscene” with all their tactile features to the figures here playfully threatens the spectator.

Emma Cousin, Noughts and Crosses, 2021

Oil and oil stick on canvas, 230 x 140 cm

Courtesy of Niru Ratnam Gallery and the artist. Photo, Damian Griffiths

As Emma Cousin stated in the presentation of her last exhibition at White Cube, Introductions, don’t be fooled: “All of the backgrounds in these paintings are graduated to suggest depth – the figures are not trying to get out of the painting, they’re trying to get further in”.[2] Although the figures never dive entirely into the screen’s depths, they remain visible at the centre of the scene, as if they claimed to be watched. In Charades, for example, five figures wedge into each other’s orifices of eyes, nose and ears in a top-down perspective. These naughty and disruptive figures never isolate but look for each other to stand against the observer on the wall, pictured in “nuclear” colours, as the artist defines them.

The spatial and physical relationship between the bodies and space is fundamental: just as if we were playing, sharing theatre’s essential traits of fiction and masquerade, this works by Emma Cousin stage the temporary and artificial construction of human relations, society and everyday relationships –– as well as arts themselves. In games and theatre, those who play participate in fiction, inviting their interlocutors to join them in a limited time and space frame to that very invention.[3] As soon as the fiction is interrupted and the game ends, the curtain falls, the joke is no longer funny: after all, we are all part of it.[4]