On Investigations of Orality to Understand the Instability of the Human Condition

An interview with Siobhán Tattan around her new work Whisht So commissioned by The Dollhouse Space in 2020 and exhibited in March 2021.

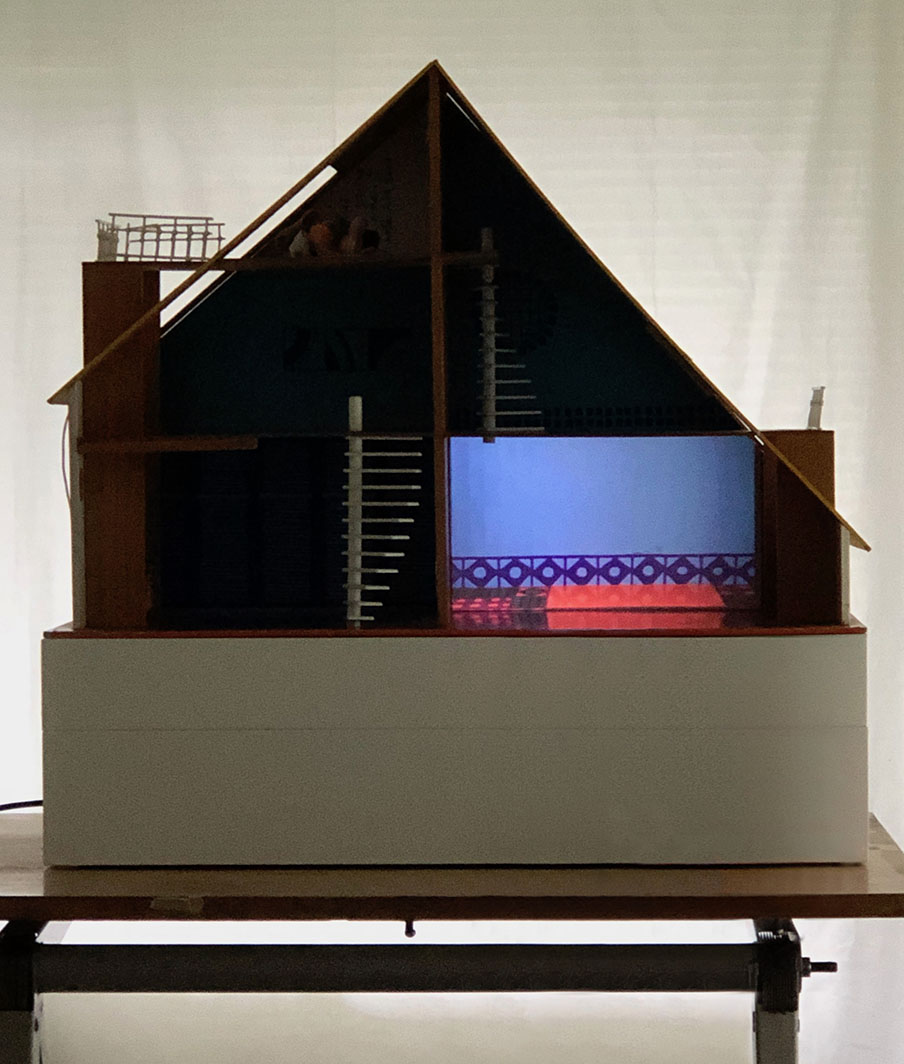

Siobhán Tattan, Whisht So, 2021, digital video with sound, 3′ 49”.

Installation view at The Dollhouse Space

What happens when thoughts materialise in words but no one is there to hear their spoken form? Can those words pile up, layer on top of one another, cover the floor, line the walls and fill a physical space entirely? In the absence of anyone to receive them and understand their meaning, will they amalgamate into an undecipherable sonic mould and slowly disintegrate, or grow in complexity into a neurotic glitch?

Siobhán Tattan’s recent work Whisht So examines this predicament. In the 3:49 min video, predominantly a single slow panning shot across the ground floor of the Dollhouse and animated by dramatic lighting, we are gradually introduced to a voice who we hear repeating a series of phrases that seem to have special significance to her. She is engaged in ‘word hoarding’, an oral and literary practice that has equally occupied Tattan during the recent lockdown. As we progress, the voice becomes increasingly distressed and the phrases become layered and harder to follow, until finally we hear a poignant ‘whisht a while’ (translation: quiet now).

Commissioned by the Dollhouse Space in 2020, Whisht So deconstructs the effects of isolation on its unseen protagonist, along with its related increased levels of anxiety and loneliness. Exhibited in the living room of the tiny, physical Dollhouse Space as well as in all of the Dollhouse Space virtual rooms online, Whisht So draws attention to those, whose spoken language does not conform to the situated norms and yet carries an affirmative quality of its subject’s cross-generational authenticity. In the following interview, artist Siobhán Tattan elaborates on the present, past and future of her work across digital media and physical-site-specific installations.

Jaroslava Tomanová: Siobhán, the central focus of your recent work Whisht So, currently screening at the Dollhouse Space, is language and what you call “word hoarding”. Would you like to explain how have you come to these themes and what makes you interested in them?

Siobhán Tattan: This project began last year after the original lockdown was extended and it gradually began to dawn on me that normative social and cultural patterns would not be resumed for some time. The pandemic’s reliance on digital communication was one motivation for undertaking a year of ‘word hoarding’. I wanted to return to the utterances and phrases voiced by my mother, grandmother and neighbours of back home. I viewed The Dollhouse as a method to catalogue this vernacular, by creating an aural dwelling.

This undertaking led me back to a favourite, Seamus Heaney’s translation of Beowulf, a book I keep finding myself returning to. When Heaney undertook this translation, he was living in America (teaching at Harvard). For him saying ‘yes’ to this project was to create ‘a kind of aural antidote’, a way of ensuring his linguistic voice would remain anchored back in his homeland of Ireland. When considering how to frame his version of the translation, he quickly decided he wanted the poem to speak of, ‘a familiar local voice, one that had belonged to relatives of my father.’ Using this method he preferred ‘to let the natural sound of sense prevail over the demands of convention.’

For me this method of ‘word hoarding’ allowed me to aurally meander back home and remain connected with those that I miss during a difficult time.

J.T.: You have told me that you are interested parochial phrases and material qualities of language, such as its tactility and spoken form. To me this sounds like you are responding to, or perhaps questioning, the normative processes which require us to speak and write in “the proper” way, one that is considered to be formally flawless. As an artist born in Ireland but currently living in Amsterdam, how do you relate to these issues?

S.T.: When I first moved to London from Ireland in 2002, I quickly and frequently encountered an inherent bias against the Irish voice/accent. At first it shook my confidence, I felt embarrassed that my language or spoken tongue was lacking sophistication or intellect. It was discovering Seamus Heaney’s translation of Beowulf that gave me the confidence to embrace the language and spoken dialect that I grew up with. Quickly this use of language became a focus of my art practice.

Siobhán Tattan, Whisht So, 2021, digital video with sound, 3′ 49”.

Installation view at The Dollhouse Space

J.T.: Having seen some of your previous works, I am interested in the formal aspects of your work. You write scripts that are performed and paired with videos and site specific installations. In Whisht So you seem to have completely abandoned narrative, which used to have quite a strong presence in your previous video works, and moved towards a cacophony of phrases that somehow overlap and blend into each other. Could you explain how you relate to this change in your work with sound?

S.T.: The work is responding to the current pandemic, of long periods spent in instructed isolation. To construct a narrative during these periods to me didn’t feel relevant. I was thinking of the elderly who for their own protection had to endure stricter lockdown measures, which led to increased levels of anxiety and loneliness. By creating a somewhat random collection of phrases, idioms, and concerns was my way of exploring this time period.

J.T.: In Whisht So, the camera moves horizontally through a space that resembles an empty house with colourfully painted walls. Space, seemingly empty, devoid of personal belongings or bodily presence of your characters, is something that has appeared also in your previous works, such as The Steep Place of Strangers. Can you tell me what makes you interested in this particular kind of absence and makes you focus more on voice or other ways to express presence of a character?

S.T.: L. Austin’s use of the term ‘performative’ ignited my interest in experimenting with methods within my practice which, when deployed, infer action or movement. In his interpretation of ‘performative speech’, it is through the utterance of a statement of means that the speaker performs a particular act rather than an action itself.

I strive for methods in my practice that could transpire to reflect unseen drama or action. I deploy such methods, to not only test their potential to intimate unseen movement or drama but also utilise these methods to convey or direct the viewer to more complex themes at play in the work, such as a personal understanding of the instability of the human condition.

Siobhán Tattan, Whisht So, 2021, digital video with sound, 3′ 49”.

Installation view at The Dollhouse Space

J.T.: The important references in your work have been early 20th Century Irish authors such as W. B. Yeats’ and Flann O’Brien, could you explain why do you find them relevant for your practice and how has your relationship to their work developed over time?

S.T.: For me these resources not only reveal significant historical points in Irish history but are also keys texts in early experimental writing.

In Yeats’ 1903 manifesto The Reform of Drama, we find his desire to challenge theatre practices, which he exerted through his dance plays. Yeats’ approach was to lift his dance plays out from the restrictions of theatre by asserting that a “stage is any bare space in a room against a wall” – an affirmation which pre-empts the performance movement. Yeats also restricted the movement of the actor so that a heightened sense of expectation can be placed on the voice in order to prioritise drama.

In my own practice, I experiment with presentations of staging, language, sound, voice, and film to test how they can uphold moments of drama. I am also interested in deploying these methods in order to provide insight and explore the subtleties of the relationships that may have occurred within such obscure moments, such as Walter Rummel’s impromptu piano recital for the cast of Sean O’Casey’s new play The Plough and the Stars, or Flann O’Brien’s self-perception of his failure. This interest in the fragility of the human condition is an interest that has grown in my practice.

J.T.: The Dollhouse Space, existing since 2018, invites interpretation of a physically tiny, quasi-domestic space and its (theoretically) infinitely expandable virtual coequal. The digital aspect originated from the Dollhouse Space’s aim to support artists who are parents or carers and whose possibilities to travel for residencies and exhibitions are limited. Could you reflect on what it was like to engage with the architecture of the Dollhouse Space? Did you feel like you engaged with your work and practice differently than in a normal white-cube gallery?

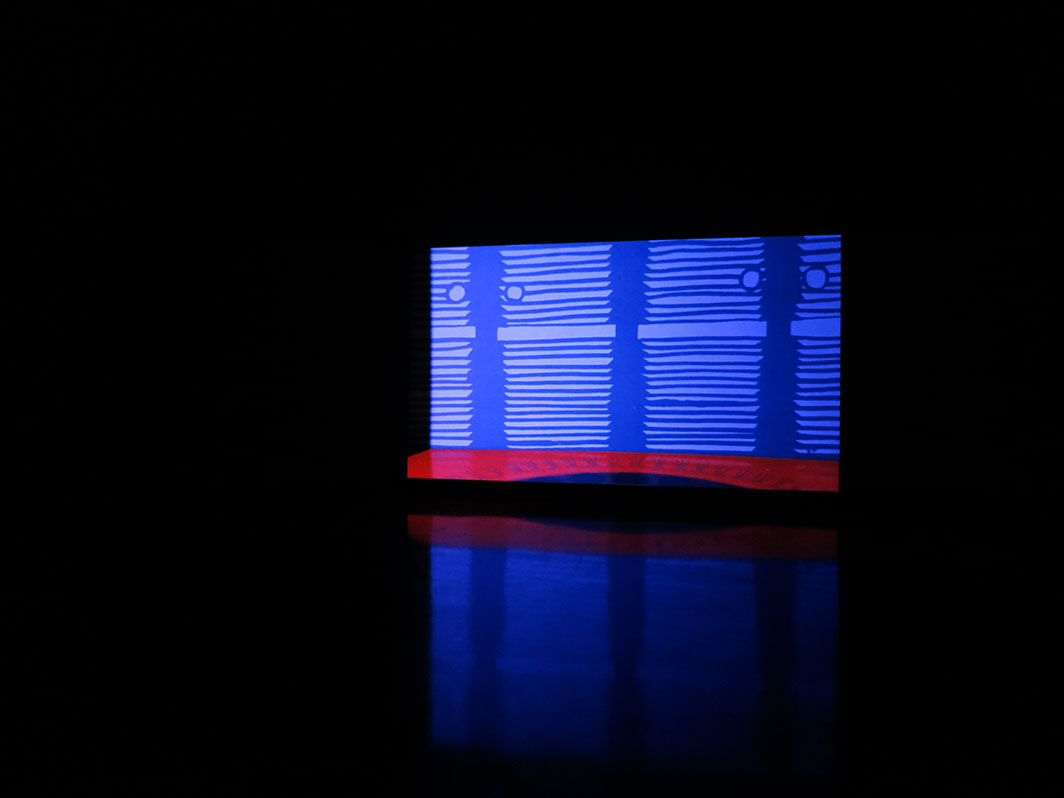

S.T.: In the past I frequently worked with muted colour schemes, it was where my eye tended to get drawn to, as this colour way suited the scripts or narratives I was working with at the time. However, working with the scale and intricate details of The Dollhouse was a great challenge and what excited me the most was its, almost lurid, colour palate. I decided to emphasise the intensity of its colour scheme further by installing RGB lighting into The Dollhouse. This was done, not only to accentuate its dimensions, but also to create discord within the space as the camera moves from room to room. I felt it best reflected the tone of narrative. The accompanying script is frantic and burdened with an anxiety of loneliness and uncertainty. The restrictions of scale of The Dollhouse fed this work perfectly.

Siobhán Tattan, Whisht So, 2021, digital video with sound, 3′ 49”. Video still

J.T.: In terms of the current situation of global pandemic, recurrent lockdowns and uncertainty around exhibiting in a physical space, I am interested in how exhibiting in the digital space makes artists think about their practice. I am often asking artists whether they have considered any changes in terms of their methods or research interests, not only as temporary practical strategies of troubleshooting during the lockdowns but rather as something that might stay as a long-term focus. Have any major shifts in terms of how you think about your practice emerged during the past year? What are the directions you would like to take your work in the future?

S.T.: I feel my working methods have stayed the same over the past year. My working pattern isn’t very structured as I work very intuitively. I normally work slowly on a project and let it evolve over a prolonged period. This usually begins with a long research period, where I am thinking, reading, writing and experimenting with materials around my chosen subject. And I feel that won’t be changing anytime soon.

Whisht So if anything, is a return to common themes that frequent my practice – these being: investigations into oral practice, use of theatrical staging methods and experimenting with filming techniques. This work, along with my earlier works like A Yearning Deep Enough, The Steep Place of Strangers and The Listening Watch, explores the human desire to find affinity with another. I am interested in the condition of the unloved outsider, which often coincides with an affliction, that of human being’s unbearability to themselves.

Often I use literature as a methodology for questioning this aspect of the human condition. Christopher Hamilton, a philosopher who utilises literature in his quest to unravel the profound instability in which humans exist, states that literature, “is far more content to open up, display and explore the surd aspects of human life without then supposing that there must be some kind of resolution.”