Neutral descriptions, and much counting…*

Critical text for the show of Peter Richards, Intuitive Actions, Common Attributes and Isolated Incidents. Millennium Court Arts Centre, Portadown, September – November 2014.

Peter Richards, preparation for and anticipation of, 2014. A 12 minute action with an Electrosonic ES3601 Presentation Unit, two Kodak carousel projectors, a section of 16mm leader, and a 12 minute endless audio cassette. Dimensions variable. 1978

In conversation with Peter Richards in Belfast on 1st May 2014, Richards speculatively proposed application of a tagging system to the documentation of performance art – voluminous in quantity and disparate in form – to aid archiving while preserving a multi-perspectival, non-linear view on the history of performance art. Somehow, I find this idea of tagging (an inherently subjective and idiosyncratic system) appeals to an attempt to analyse and understand the themes and processes at work in Intuitive Actions, Common Attributes and Isolated Incidents. Appropriately, application of the method demands my drafting a list…

Tags: Performance art, Time, Borders, Conceptual art, History, Blinds, Chairs, Beckett, Technology, Language, Obsolescence, Fragility

Intuitive Actions, Common Attributes and Isolated Incidents exacts a performance’s ransom on its audience: it dares to demand our valuable time on its terms. Richards provides no relief from the real-time experience of the old video works – he denies viewer customisation (the facility to speed back and forward, selectively viewing bits here and there), he saddles the works with lengthy titles (plausibly artworks in themselves) and designs sculptural obstacles that prohibit a quick “run around” the exhibition. As a carefully constructed environment, the exhibition space itself serves as the structure within which a conscious “experience of time” is made possible.[1]

Richards revisits, but does not necessarily revise, old works and, represented against newer pieces in the exhibition, these works simultaneously lose and gain meaning. Untitled: Live Video Interaction. Exercise 1 is an important conjunction between the older and newer works, marking a significant point in time; a moment poised on the cusp of the digital ‘coming of age’ when emailing a livebroadcast television show was a radical gesture, making use of cutting-edge technology. In the interim we have grown accustomed to high-definition visuals, highfidelity sound and pocket sized, high end communication possibilities. Aligned against these, the tech relics occupying the gallery become endowed with certain museum qualities acquiring, in their aged state, a vague air of functional mystery, making a virtue of “grit” and evoking, in the viewer, a sense of nostalgia and a geeky fascination.

But there is a plodding graciousness in the behaviours of the technological dinosaurs at play in the space: they grant the audience exceptional permission to decelerate, gently encouraging the viewer to adapt their pace to that of the slide projector, the reel to reel audio, the real-time playback of the SVHS tape. By contrast, our slender smartphones seem crude and out of place: their rhythms feverish, their updates and reminders expressing a faux urgency.

Richards takes a sculptural attitude toward semantic and narrative content. In an email exchange he explained that he is interested in the “materiality” of the text: “maybe I’m attempting to use it rather than read… there is something of its materiality rather than it being a means of conveying its idea that interests me in relation to my attempt to create a fragile boundary, a perimeter, wrapped in the contradictions implicit in translation… maybe that’s a starting point, the act of extracting… lifting from context… helped further by frequent re-reading it becomes more and more concrete or do I mean plastic…” For Richards, this process of familiarising, to the point of transcending contextual meaning, renders the text sufficiently pliable to manipulate as a sort of three dimensional substance of itself.

Peter Richards, A perimeter, a futile exercise in cartography, 2014. A sculptural installation with audio featuring a reading by Elisa Nocente of an extract from H. Marcuse’s An essay on Liberation. Recorded on quarter inch reel-to-reel tape, looped, and played back across a system of reel-to-reel players. Accompanied by a repair kit mounted on a plinth, comprising a splicing block, (last used to edit an omnibus edition of the Archers in the early 1980’s) blade, tape and note.

Richards’ research also weaves through readings on Structuralist film theory and this sensibility reflects in the work. There is no narrative hierarchy in Intuitive Actions, Common Attributes and Isolated Incidents – the pictorial, personal past, explicitly referenced in Stopping the Spots and Action, suspension, tension and (quite likely) self-destruction, is not used to load the work with added emotional agency or pertain to autobiography. Rather, personal narrative is subordinate to the “sculptablity” of the content: the images in Stopping the Spots selected on the basis of the harmonious pattern of the burn holes and in Action, suspension, tension and (quite likely) selfdestruction the sections of film are selected for their durability, rather than any emotional charge.

In A perimeter, a futile exercise in cartography a female voice softly intones an extract from Herbert Marcuse’s (1969) An Essay on Liberation. As the tape plays through three reel to reel tape players the reading is punctuated by terrible moans – it sounds as if the strain on the tape afflicts the medium itself or perhaps these are cries of protest, a “drowning out” or an exercise in self-censoring – until, eventually, the voice is muted completely. The intermittent groaning continues…The sculptural content mutates with time and the piece, while bearing traces of its history, manifests as a different work at the end of the exhibition period.

As an act of understanding and generosity (it is conceivable that some unfortunate viewer will stumble into and snap the tape or will witness its snapping under its own tension and feel, in witnessing, somehow responsible), Richards supplies a “pseudo repair kit”[2] (splicing block, blade, tape and note) – reminiscent of museum displays of primitive tools belonging to prehistoric human cultures (like Stone Age flints and spearheads), the simplicity of the vintage instruments harbouring secret knowledge about their use, the skills required to utilise them now the preserve of “specialists” in a minority field. (In the same way that I wouldn’t know how to skin a boar with a sharpened stone, I wonder if a digitalnative would know how to use the tools to repair the film strip…).

Within the exhibition Richards’ single concession to ubiquitous modern technology – his smartphone – he holds discreetly, using it, primarily, as a sort of metronome to pace his count in preparation for and anticipation of. Amusingly, the function of this talented multifunctional device is reduced to one which any of the analogue machines could easily manage. For a period of twelve minutes, corresponding to the length of a stretch of endless tape, Richards repeatedly counts down from ten to zero, in a uniform beat measured against three consecutively streamed recordings of Franz Schubert’s Nacht und Träume[3], played on the smartphone. Drifting in and out of the countdown I start to wonder if I’ve missed something: An instant? An epoch? An anticlimax? Or is he rehearsing for a future event? Like the slow erasure of the voice in A perimeter, a futile exercise in cartography, the artist’s own voice wears a little thin and raspy toward the end of the twelve minute performance and conclusion comes as something of a relief. Somewhat absurdly and self-consciously, in the attitude of an out of date performance art audience, we applaud the end of the count in the way a proud parent might applaud a three year old a similar achievement.

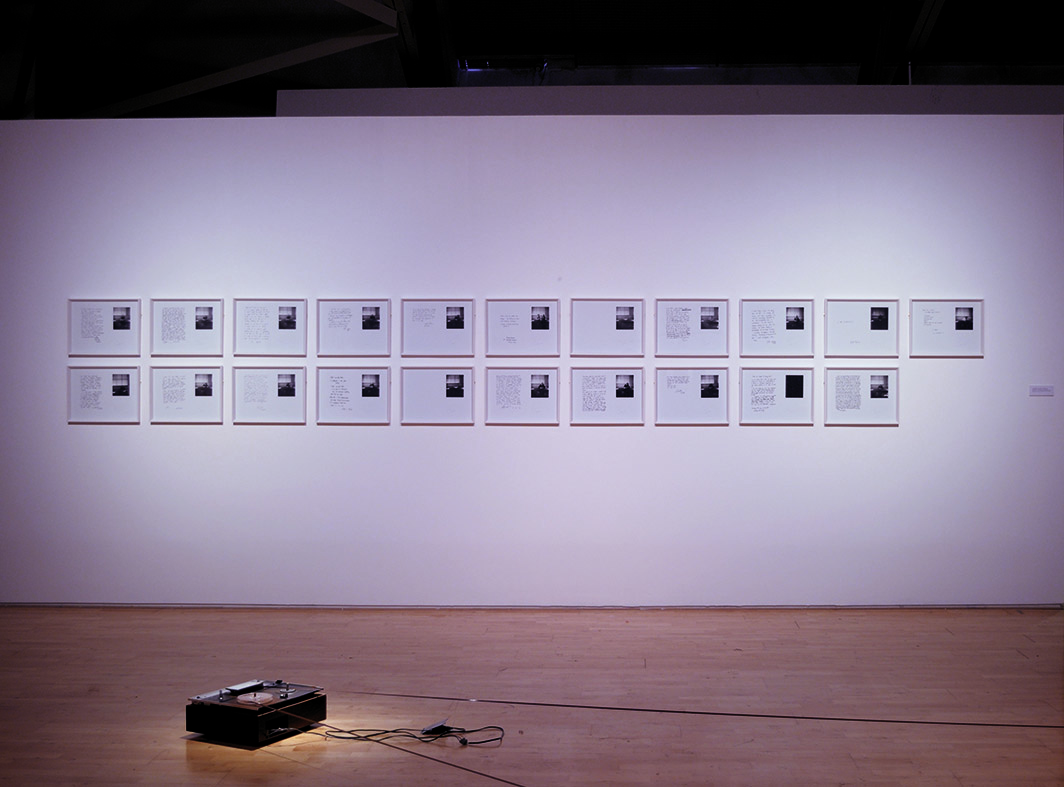

Peter Richards, 21 Variations, 2014. Textual and pinhole photographic documentation recording the responses of individuals, invited by Kim McAleese, to a previously undisclosed question. Series of 21, 16 x 12 inch framed silver gelatin prints. Edition of 5.

And yet our passé response feels not quite out of place – in fact, Richards himself, soberly clad in black from head to toe points out, with a grin, that he is dressed in the uniform of a performance artist from the 1970s. He could almost be a Bruce Nauman tribute act performing a variation on a studio theme; the scraping of metal chairlegs on tile and the metallic thuds echoing from Untitled: table & chair exercise 9.1, serving as ambient background noise to the live countdown, like a soundtrack of 1970s performances (though these sounds issue from recordings of performances made in the 1990s…).

Beneath the surfaces lurk language games and Conceptual art jokes. The exhibition title itself reads almost like an academic task in linguistics or a programming command: an instruction to scan a document for common adjectives, isolated pronouns, active verbs. We feel compelled to make connections, to join the “isolated incidents” into a “coherent event” – and, somehow, the works both facilitate and resist this inclination, embodying debts to Lucy Lippard’s seminal curatorial project, Six Years: The dematerialization of the art object from 1957 to 1972, bringing together a contested “collection” of individual artists and ideas into something later approximating a Movement.

And shadows of members of Lippard’s cohort loom large in other corners of the exhibition too. The spirits of two stalwarts of this Conceptual art movement, Sol Lewitt and Joseph Kosuth, hang around the gallery walls leaving ethereal thumbprints on …not (a) beginning …[4] and Star Dust: Prototype Death Chair. Indeed, guided by the descriptions supporting the titles, we could be forgiven for mistakenly ascribing these works to an older Master. StarDust: Prototype Death Chair (surely an easy candidate for carbon dating!) claims 1970 as its date of creation (long before the Star in question was born, let alone met her death…) but, as with several other works in Intuitive Actions, Common Attributes and Isolated Incidents, Richards takes a free hand with chronology and assigns this present day painting a date that he feels is more “authentic”, more art-historically accurate.

A painting of a chair – no chair in particular, yet at the same time, the ultimate chair, the chair that encapsulates the essential chairness of chair. A painting of a chair that is bound in conversation with the Great Chairs of Conceptual Art but, like a Star Wars prequel, this “prototype” chair comes after Kosuth started the series in 1965[5]. Like many of the artworks spending themselves within Intuitive Actions, Common Attributes and Isolated Incidents, tending toward their imminent end, this chair too is redolent of death. Cat ash, star dust: flecked with magic and tarnished with some awful Warholian reminder of more sinister associations of death and chair[6]. Prototype. Perhaps this painting itself is a kind of rehearsal…its title poetic, sad and funny all at once…

Peter Richards, Untitled: Live Video Interaction. Exercise 1, 1996, S-VHS, Video documentation of a performance collaboration with a mobile TV crew from the 2e Recontre International d’art Performance, curator R. Martel, Quebec in 1996. Duration 25 minutes plus.

Immediately greeting the visitor upon entering the gallery space, …not (a) beginning …, a temporary wall painting, while utterly unavoidable (unless one ascends the stairs blindfold) professes to be other than an obvious opening to the exhibition. I begin to wonder if I should read this title as part of a labelled list: …not (a) beginning, nor (b) ending, nor (c) either of the above…

The brick red text, a negative impression from vinyl lettering, abstracted from Samuel Beckett’s 1958 one act play, Endgame, is ambiguous in tone: “Mean Something! You and I! Mean Something!” Is this a command? A terrible existential plea? A revelation? A prank? (a nod to the stockintrade humour of the YBA – now more youngish than young). Falling safely under the 140 character count, I find myself considering its potential as a Tweet.

Again Richards plays with language and philosophical double stops. He frequently works in collaboration with other artists and, perhaps, nested in …not (a) beginning …, the most subtle (or, arguably, the most obvious) collaboration lies. If the “and” is additive: (You + I) = (Meaning Something) interacting with the works, an audience fulfils the condition set forth in this equation. If we choose to admit Kosuth’s hypothesis that “art is making meaning” it could be argued that this work proposes that the intimate, private collaborations between the audience and the works within the exhibition generate the art itself.

[pause]

[Brief laugh] “Ah that’s a good one!”[7]