Narratives of Otherness: Metaphysics, Georgian Contemporary Art and Its Few Strands

A post factum accompanying essay written in May 2020 about the exhibition New York Meets Tbilisi: Defining Otherness (January-May 2020; Part 1 & Part 2 at Assembly Room and Kunstraum LLC, New York) that is also an overview of the processes in contemporary Georgian art.

A positive affirmation of local values later turned into contempt for outsiders.

Mario Vargas Llosa, Nationalism and Utopia

What is darkness without light?

Akutagawa Ryonoske, Life of a Fool

What is hell? Hell is oneself.

Hell is alone, the other figures in it

Merely projections. There is nothing to escape from

And nothing to escape to. One is always alone.

T.S. Eliot, The Cocktail Party, Act I, Scene 3

Otherness is something that exists inside and outside of ourselves. In this essay, I will take several approaches to investigate it. First, I will look at it through a more philosophical prism, considering micro and macro levels; second, I will look at the same notions within the contemporary as well as traditional Georgian culture and art, and lastly will conclude with a brief overview of the selected works of my exhibition New York Meets Tbilisi: Defining Otherness presented in the winter-spring 2020 in New York as a few examples of my curatorial approach. The goal for this essay and the exhibition that inspired it was not to look at larger theories of colonizer and colonized, influencer and influenced, metropolis and periphery, but to understand positioning of the Other as an inherent part of a larger and complex dynamic of the contemporary cultural landscape.

I. Metaphysics of Otherness

As a concept imposed onto the macro, external reality the Otherness is a fundamental one for understanding our social or personal roles, system of relationships, rules in the contemporary society, definitions of our collective experience as well as more subjective and subversive structures of our inner lives.

Concept of ‘Other’ and ‘Otherness’ is a fragile, too broad or too narrow, depending on the context and who is using it, depending on his or her essence, skin color, emotional makeup, cultural baggage, and class. The frames and contents of this entity keep shifting just as our identities shift and change from one particular point to the next as we go across our life shifting and discovering pieces and strands of ourselves; some parts of these newly discovered elements could remain hidden, untouched, almost taboo because of the prejudices we have internalized about ourselves and others.

Other is always there, to the point of us completely forgetting his, her, or their presence, yet without him/her/them we also cannot be ourselves, we only exist in opposition to something outside of us. This contrast of the Self, in-group, Us and the Other, outsider(s) is a dichotomy that has widely permeated the philosophical and religious discourse of being. Hegelian phenomenology posits the Other at the center of our Being, self-consciousness exists only when projected towards another entity and we can only be defined in continuous opposition to it through “the return from otherness (die Rückkehr aus dem Anderssein).”[1] It is noteworthy, that this process of discarding the other is dynamic rather than a fixed one, it is ongoing, governed by laws of life. Such self-reflective mode of continual negating provides for a limitless and moving Being, completely attached to the Other and not able to exist outside of its presence. This attachment is eternal as the self is defined by not being the Other, rather than by the individual attributes.[2] This assertion though highly abstract rings absolute truth when contemplated in relation to dynamics of human lives. Continuously developing as we go, defining ourselves in opposition to what we are not.

If considering Lacan’s definition of the term, and he devoted a fundamental place to this term in his discourse. Lower case other for Lacan is not a physical other, but a reflection or a projection of one’s weak human ego in the Imaginary register, the domain most closely related to the conscious life within his sophisticated blueprint of the human psyche. This ego goes through Oedipus complex that in difference to Freud has m(Other) as its center. As a child grows and develops psychosocially the figure of an overbearing or absent mother is at the center. Hence, she becomes more then reflection of one’s ego, but rather a capitalized Other of the symbolic register, domain of institutions, rituals, rules, traditions, a stuff of one’s myth. Once m(Other) figure is ascertained, different entities from this domain become important (father figure, language, laws). Thus accordingly, other and Other are at the center of our conscious and subconscious existence in one way or another.[3]

Besides Hegel and Lacan, philosophers who contributed most to the discourse on the Other and Otherness include Plato in his most mysterious dialogue Parmenides, Martin Heidegger in Being and Time, Emmanuel Levinas, and Jean-Paul Sartre. Similarly, Plato’s Parmenides outlines difference (otherness) as an attribute of time and spatial location, while also a main predicate to Being, as the latter is a priori defined by Sameness, the unified One.[4] Heidegger terms Otherness as ontological difference that is crucial for his delineation of Beings and beings (entities), the main divider for Dasein – our existence as humans, and Being is of the ultimate interest to him.[5] Emmanuel Levinas takes on a social context as a philosopher as Otherness, declaring that the Other is indeed what I am not, that my relationship with the other is that of transcendence, the same kind of transcendence as achieved when in communion with death.[6]

As the major element largely defined through absence rather than presence of inquiry into the aspect of Being, question of the Other and all the issues coming from it, became a big unifying force of the Western philosophy, certain strands of which could be traced through responses to these particular inquiries. Intuitively we tend to see the problem of the Other, as of someone or something outside our control, and hence a constant source of anxiety because he/she/it evaluates and objectifies us in return just as Sartre theorized.[7] This anxiety breeds the desire to defeat or dominate the Other if other favorable conditions exist, creating what Tony Morrison termed “master narrative.”[8] A single narrative that is based on particular social, economic, political, historic, psychological, emotional conditions that creates the delineation of otherness or separateness, space for inclusion of a particular set and subsequent exclusion of another set of entities or individuals. Cultures and societies have continuously been built upon the ambiguity surrounding this vague concept. Wars were fought in the name of defeating ‘other’ ideologies, ‘other’ religious or economic values, ‘other’ understanding of realities that could not be reconciled with our own be it on nationalist or cultural basis. As long as the human race exists it has been ‘us’ versus ‘them’ and ‘they’ always continue to be different because ‘they’ cannot be fully understood and completely seen if not juxtaposed by ‘our’ own premises and believes. On a macro scale of a state, Otherness could be traced in postcolonialism and contemporary nationalism sweeping many Western countries.

Edward Said’s book Orientalism, published in 1978 is of course the most well-defined attempt to confront the theme of Otherness in the historical and social context within the framework of structuralism. Said’s primary concern is with the mutual and interdependent binary opposition of central self and decentralized other, emphasizing that construction of the ‘otherness’ of the other is actually covertly and simultaneously the means of constructing, defining, delimiting the nature of selfhood, or in case of the Orientalism, of what it means to be Western.[9] It is the same mechanism as outlined by Hegel above.

Cultural theorist Homi K. Bhabha (b.1949) continued addressing Said’s enquiry by looking at the Otherness as integral part of post-colonial intellectual project. It is noteworthy that Bhabha views Otherness as a rigid attribute, something that is fixed in time, memory, and representation. If Hegel insists that working through addressing Otherness as an individual is a self-reflective and dynamic process that arises when one encounters any new particular ‘Other;’ Bhabha looks at a rigid set of racial and sexual stereotypes that we need to overcome. To him this ambivalence is created by asymmetrical relations of self/other, master/slave, knowledge/disavowal, mastery/defense power struggle. Another important contribution by Bhabha is an illuminating concept of mimicry as a surviving mechanism of the colonized to fully take on the identity of the colonialist, thus fully losing one’s own. What mimicry does is it overwrites the narrative imposed by political and social power onto local landscape, while never fully fitting, always having spots that do not align, thus only proving marginally representational of the authentic.[10] Mimicry became an ever-present factor for the ex-colonies of the West in the last as well as this century, a trend continuing in the Eastern Europe and its societies today discussed in the next section.

The other side of this revisionist attitude towards history of colonialism that is fully pertinent to the discussion of Otherness is of course resurging nationalism. A force globally on the move from Western Europe and the United States to the South America. Fear of the outside world solidifies fears inside a society, as members are becoming more intolerant towards the outsiders.[11] As such fears need to be mitigated a call toward a more traditional, heteronormative society is what is required to supposedly solve our ills.[12] Passion for the local and the authentic, for old and traditional that nationalism offers gives a perfect mask for any kind of intentional inability to relate to the Other.

Before closing It is important to consider, yet another relevant aspect of Otherness and that is from the perspective of the Feminist theory. Existential philosopher Simone de Beauvoir investigated the phenomena in her books Second Sex and History of Sex, published in 1949 and 1961 respectively. In them de Beauvoir traces the emergence of the Other as always in opposition, something less certain, mysterious, hence it is always the woman that is the Other in the established systems of patriarchy. “Eve given to Adam to be his companion, worked to ruin the mankind; when they wish to wreak vengeance upon men the pagan gods invent woman; and it is the first-born of these female creatures, Pandora, who lets loose all the ills of suffering humanity. The Other- she is passivity confronting activity, diversity that destroys unity, matter as opposed to form, disorder against order.”[13]

Other feminist authors such as Cheshire Calhoun, Betty Friedan, bell hooks all followed the similar line of reasoning whereupon, the social conditioning of women inside the patriarchal system in the end determine their self-identification with the docile social and sexual roles as prescribed by men, while the ‘wild’ creature guided by her emotions and instincts always remains the dangerous Other, in constant need of guidance and control. Femme Fatal becomes the embodiment of such Other, a woman who is not scared to use her ‘feminine charms’ to get what she desires, often at the expense of man’s life and sanity.[14] The Otherness of women becomes even more underlined when there is a minority religious or cultural identity involved, then women could be truly defenseless against the outside prejudice as well as from her inner self-consciousness.[15] Othering and Otherness based on sexual orientation and race is another big aspect, but I am leaving it out of this text as all of the aspects require their own separate sections and could not be covered in one relatively short essay.

Contemporary reality with its roots in poststructuralism and underlined validity of multiple meanings to a single set of raw data, liberated larger cultural discourse into something less fundamental. This discourse is more fragmentary, giving each hypothesis of internal or external Otherness a right to exist and discussion of it is more than ever relevant. However, on the other hand, Otherness is also part of micro, internal lives of our psyche, where various parts collide and not always coalesce into one harmonious hole. Otherness or alienation of this intrinsic sort becomes even more difficult to pinpoint and pin down, to analyze and define, because it connects directly to charged ideas of self-perception, ego, and acceptable norms of any given society, deconstructing or reconstructing it becoming hard. In a context of personal narrative Otherness could be a mental illness, a sexual part of us that feels alien and forbidden, parts of our personal history that could feel alienating and so less integral of the story we tell to ourselves. I will address these perspectives in connection to the individual artworks in the last section of the essay, turning now to a few historical narratives of Otherness in the country I am from.

II. Narrative of Otherness in the Georgian Culture and Art

The story goes something along the lines of (as directed to a foreigner): there is something wrong with us, something dark, and violent and backwards about our mentality. We are victims of our own selves, and a world that can’t ever understand us. It says: we are fascinating surely, and you may even find it sparks desire. But don’t try to understand us (we barely understand ourselves). It implies: Simply watch. Marina Abramovic[16]

Artists in the West are not lazy and therefore not artists but rather producers of something… Their involvement with matters of no importance, such as production, promotion, gallery system, museum system, competition system (who is first), their preoccupation with objects, all that drives them away from laziness, from art. Just as money is paper, so a gallery is a room. Artists from the East were lazy and poor because the entire system of insignificant factors did not exist. Therefore, they had time enough to concentrate on art and laziness. Even when they did produce art, they knew it was in vain, it was nothing. Mladen Stilinovic[17]

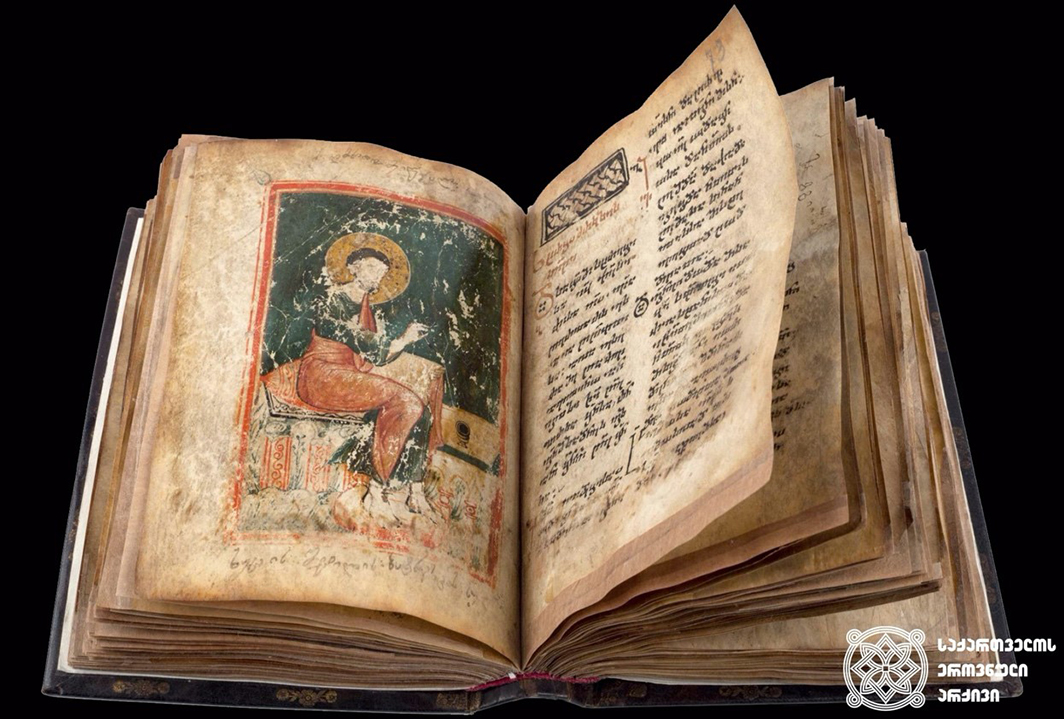

Etymology of the word Otherness in Georgian is written as უცნობი, უცხო (‘ucnobi,’ ‘uckho’), something or someone who or what unknown, places where one has not been to; something not belonging to your homeland, something that is not your own; something superfluous, not needed, not acceptable; out of the ordinary and noteworthy. Grammatically these words are related to similar words შეუცნობელი, უცნაური that denote something that cannot be fully known or defined, something beyond one’s understanding. Going back to Lacan who brilliantly ascertained that unconscious is structured like a language[18] we also know to what a deep extent language structures our being, so words matter. The simultaneous apprehension and fascination with the figure or entity of the Other in a concrete or abstract disguise, in the form of the historic past or historic present expressed in the etymology of the word encapsulates a narrative of this phenomena in the Georgian history, thoroughly mirrored in its art. As is the case with many old countries with interrupted histories,[19] Georgia leads a double life, while living in the past, living concurrently in the present.

The past or rather unconscious clinging to it is, in Jungian terms is a shadow, an evil doppelganger that the country needs to get rid of and/or fully internalize to achieve a full self-concept. This codependency is expressed through art as it always gives a society the most direct way of engaging with pressing contradictions. Narratives I see in the contemporary Georgian art are coming from this deep affinity that could be divided in two. First is a bigger narrative capitalizing on a de facto victimhood of the Soviet legacy, post-colonial trauma that is not always consciously expressed, but palpable in raised visual themes. A sub-narrative of this is a Georgian past akin to romanticized legends that of course is rich in traditions, talents, and achievements, but largely underrecognized outside of the country.[20] A second narrative of Georgia is a search for its geographic and hence cultural identity, search between being a unique periphery or a part of Europe, an attempt to escape to be part of Eastern Europe altogether. One consequence of this narrative reflected in art results in enhanced practices of mimicry as defined above by Bhabha, when a colonized is not yet able to write its own text, tries to formalistically follow the metropolis, in this case metropolis being the West. This happens in an effort to cater to the demands produced by the Western commercial interests (galleries in case of the art scene) as well as through genuine artistic searches for self-discoveries. Active construction of the Self is happening within the contemporary Georgian art, with more artists looking inside more than outside[21]and also through many significant Georgian artists working abroad, coming back and influencing those at home. Yet, there are a few caveats to consider within this dynamic, but first a brief sketch of the Georgian culture as it relates to Otherness.

Located at geopolitical crossroads of European and Western political powers throughout centuries the country has suffered numerous invasions, its borders drawn and redrawn as one after another empire brought Georgia under its ‘protection.’ Hence, the set of believes that sustained the national spirit over time became dogmatic and fundamental, separating social groups who were marked by these signifiers from anybody who did not. Three pillars of the national identity formulated in 1860 by Ilya Chavchavadze, a social thinker and activist of a great influence in his life and beyond, were homeland, language, and religion; in his later, 1878, revision religion changing into history.[22] Tragically, rallying around these three pillars and emphasizing that the country was only for ethnic Georgians is what lead it into a bloody civil war 1990s under the first president of the independent country Zviad Gamsakhurdia, his main slogan being Georgia for Georgians, deliberately failing to remember, as intellectual as he was, the multiethnic society of his country.[23]

These pillars constitute a core of the traditional Georgian identity, but when these elements are clashing against one another or against an outside force civil unrest, xenophobia, fears against the outsiders are exacerbated and this has been continuously repeated throughout the Georgian history, which at other times was marked by high tolerance and multiculturalism. Yet, belief in absolute, almost messianic, uniqueness underlined is shared by majority of Georgians providing them with an almost archaic understanding of the global multiconnected reality. To a large extent it has been influenced by a rise of religiosity as the main sustaining force of the national idea especially since the recent civil wars as a state was not strong enough to provide a rule of law. An important point here is that this preoccupation with either romanticizing 19th century, going back to the Golden Age of 12th century when the country was ruled by a strong king, or a hidden Soviet nostalgia is directly related to the lack of a coherent national identity adequate of the contemporary time and answering important questions of direction.[24] These periods that still have their nostalgic allure have found strong embodiments in literary arts as well as traditional frescoes and architecture. Surely, what needs to be emphasized is that the millennial generations of Georgian 20-25-year-olds today have qualitatively different attitudes toward their circumstances as well as their civil responsibilities and this is reassuring. Also, by no means Georgia is unique in this as most of post-Soviet countries are undergoing the same changes, each with their own local set of nuances.

Georgian self-perception is always clashing with the hidden Other of the Soviet past, a ghost or mental heritage that is always there as in a birthplace of Josef Stalin either directly or through its contemporary reincarnations and overt references to the post-Soviet challenges. During the Soviet time Georgia was consider the ‘jewel’ of the Union, a place to where people from all eleven Soviet republics would come for the sun, green pastures, and red wine. After the communist collapse this has changed as most of the touristic infrastructure collapsed as well. Yet, older generations of Georgians have never completely adjusted, longing for an easier life of a favorite colony. Today as Georgia has again become destination of tourists, Russian-speaking ones representing the majority, the history of an independent country seems to have come back full circle. Yet, younger generation has only a vague idea of what the Soviet period of the Georgian history represents and how corrupt, disruptive, secretive, and isolationist this time was.

Still from Arsena Jorjiashvili’s film, Dr Ivan Peerestiani, 1921.

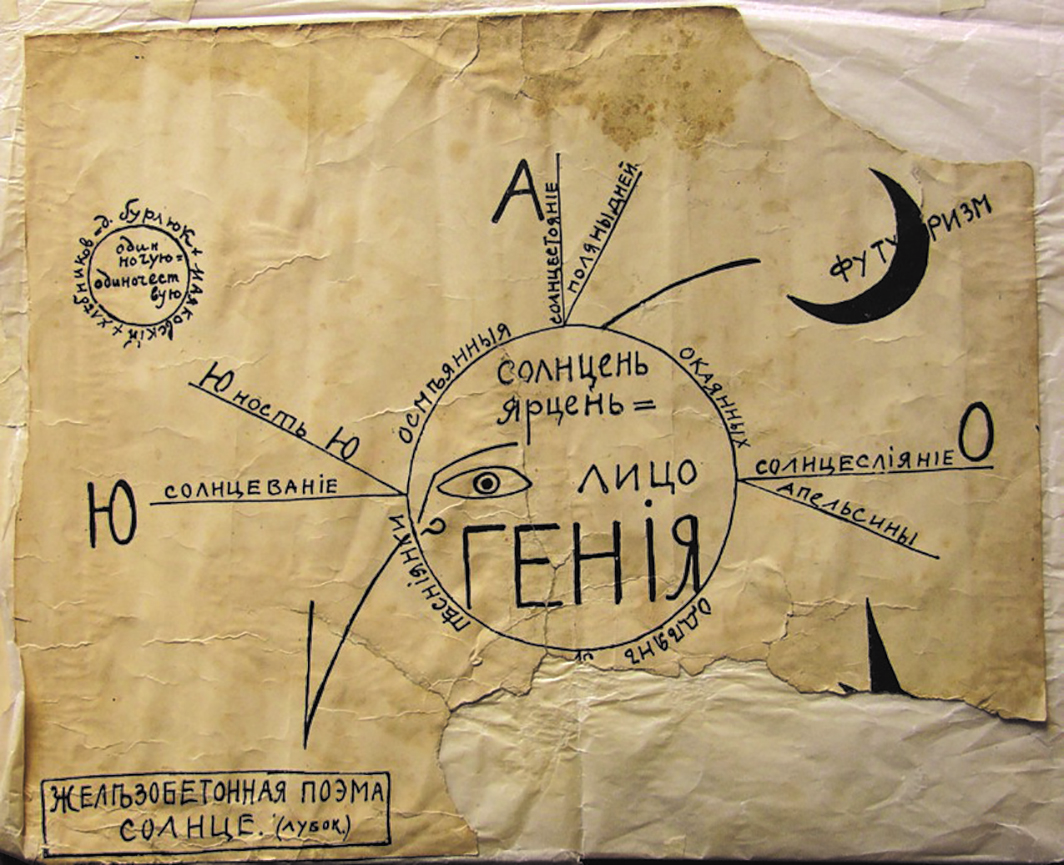

As with rest of the Eastern Europe it is problematic to understand Georgian art outside its social context, paramount role of local traditions, and question of narratives, of who is telling a story.[25] And question of smaller narratives is complicated for the entire Georgian art as indeed it has been interrupted many times over. Until the Soviet invasion of 1917 Georgian art has been systematically developing within the discourse of the Western tradition, with visible influences from Byzantium as well as from the surrounding strong non-Christian states. Yet, Georgian bohemian and cultural elite always had close intellectual affinity with Europe, its literature, iconography, and symbology, theater, poetry. Writers and artists were habitually travelling and living in Saint Petersburgh and Paris, then the center of the art world up until the world wars, bringing back current trends and influences, adding to the richness of the local art soil. Last such flourishing happened in 1918-1921 as Georgia became independent Democratic Republic with Tbilisi becoming a cultural capital of the Southern Caucasus. At this time key members of the Russian avant-garde fled to the city adding to the phenomena of the Georgian Modernism, key members being brother Zdanevichs as well as David Kakabadze (1889-1952), Dimitri Shevardnadze (1885-1937), Mose Toidze (1871-1953) experimenting with the genre. Тhis was a time of interconnection and artistic experimentation, where Otherness was not fully visible, although interestingly, is foregrounded in the current assessments and textbooks, which again reminds of trauma later inflicted to the country as the Russian, and not Georgian, origins of the Zdanevich phenomenon is underlined.[26] The unique and Other artist of this time by definition was Niko Pirosmanishvili (1862-1918), a humble and self-thought visual singer of the Georgian street life who lived in the cellar and died destitute.

Ilya Zdanevich also known as Ilyazd (1894 Tiflis – 1975 Paris) was a poet and Kyrill (1892 Kojori – 1969 Paris) a painter. They both received education in Russia, quickly becoming active members of relevant artistic groups of the day, mingling with the bohemian and intellectual elite of the time (poets Vladimir Mayakovsky and Alexei Kruchenykh, artists Kazimir Malevich, Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov among others). Futurism as framework of ideas and way of relating to reality in poetry and in visual arts, channeled through manifestos of Philippo Tommaso Marinetti, they read and admired, has deeply influenced the Zdanevich brothers as well as their whole milieu. As they came back to Georgia Zdanevichs funneled their creative energy in proselytizing futurism among cultural elite of the day and bringing new westernized meaning into old traditional forms of artistic expression, while at the same time sometimes using elements of the Georgian folklore and mythology.[27] Although Dadiasm and futurism brought by Zdanevich brothers did not become the main expression of the local artists at the time, nonetheless intense creative fuse of this period marked by multilevel stage designs, theatrical performances, musical compositions, experimental literature, various magazines, sound poetry, paintings left a definite mark on the Georgian art scene reviving towards the end of the century in the theatrical performative practices of the 1990s.[28]

With the entry of the Red Army in 1917 and announcement of the Georgian Socialist Republic in 1921, Georgian art has been radically divided in two: the official, politically correct, art sponsored by the Communist Party and following its very direct censure and limits and the unofficial art of undergound artists, living and working in semi-isolation and on the margins, following the practices of samizdat and gatherings at each other’s kitchens and living rooms. Thus, there are two sub-narratives of the Georgian art of this period extending for seventy years and unfortunately to this day only a few fragmentary accounts of these two narratives exists, outside of some separate memoirs and essays, there is no systematic study of the period. Historization of these intermingled narratives has not been created yet, thus creating further difficulties for fully understanding and presenting the art of the time to the West. This fragmentation between the Soviet monoculture, apt contemporary term widely used by political theorist Chantal Mouffe denoting a society subscribing to homogeneous cultural and ideological variables,[29] and the underground art has produced a rift in the aesthetic judgment of the common Georgian viewers as well. For them viewing art created by their countrymen as ideologically it has been termed as decadent and not worthy of the Soviet values was already conception of Otherness, these works positioned outside the dominant ideology.

As Boris Groys aptly describes in his essay: “Official art was identified as being truly “Soviet.” Unofficial art was considered to aesthetically represent the West at a time when political representation of Western positions and attitudes was impossible. That is why Soviet unofficial art was “more than art.” It was the West inside the East.”[30] Before the Soviet collapse the West for those living inside the Soviet Union had two opposing connotations. For staunch supporters of the Communism it served as the constant symbol of the Other, of decadence, gluttony, and capitalist temptations. For the covert dissidents the West was the complete opposite of the grim Soviet reality, symbolizing artistic freedoms, aspirations, opportunities, and dreams. American literature and art served as a magnet for younger generations and used book, films, any available art works as the escape tools for what philosopher Merab Mamaradshvili termed “inner immigration.”[31] The enclosure of these artists contributed to understanding of an artist’s figure outside the common boundary, of someone elitist through his or her aspiration and passion for freedom. This iconography of contemporary Georgian artists still exists in the country as the most well-known and well-connected artists come from the families of older artists of previous dissident generation, a phenomenon not unlike other countries of the Soviet bloc.

Karlo Katcharava in front of his painting, General, Image courtesy by Guram Tsibakhashvili, 1990s.

This fact was brilliantly addressed by Karlo Kacharava (1964-1994), an outstanding artist, art historian and theorist who was a leading figure of 1980-1990s Georgian art scene. With like-minded young artists Kacharava founded groups “არქივარიუსი” and “X სართული“ (“Archivarius” and “X Floor”), both creating a flurry of exhibitions and performances not unlike 1970s Group of Six Artists active in Zagreb under the leadership of conceptual artist Mladen Stilinovic. However, Kacharava’s artistic direction could not be limited to conceptual approach, but included a very vast array of cultural references and a heavy dose of German expressionism. Under Kacharava’s leadership and with his theoretical grounding and far-reaching curiosity in the modern contexts the Georgian art of early 1990s was overcoming a period of stagnation and in an group effort of experiment and cooperation was looking for novel forms. This was happening on the backdrop of civil unrest, death of the Soviet empire, massive power shortages, and economic downfall. Yet, the fuse of the experimentation was burning bright and limits were pushed. Kacharava’s untimely death at age thirty greatly hampered the natural development, although his insights, his essays, express current realities of the country just as well.

In the last twenty years Georgian contemporary art has been undergoing a major and traumatic adjustment to the historical, cultural, artistic global reality that it was to the most extent excluded from for at least one generation. Many interesting works came out from these years, yet many Georgian artists seem to follow the routes of either self-exoticism[32] or mimicry, sometimes lacking in genuinely experimental approaches as well as in universal themes, still overcoming post-Soviet trauma. This is a natural process that takes time to gain in force, local issues need to be defined and revisited before moving to the next level of artistic practice that could be interesting to the wider Western audience. A quote by a brilliant Georgian Soviet philosopher and humanist Merab Mamardashvili (1930-1990) comes to mind as he says about the Soviet period, but that could also describe the contemporary approaches: “Many of them [thinkers] tend to turn into a closed system – eternal repetition of the same conditions. Somebody who finds himself in a situation of the kind is incapable of becoming a detached observer and recognizing himself as a participant of a conditional game, never daring to question the rules thereof.”[33] Retrospective exhibitions in the format of for example “What is Hungarian?” presented at Mucsarnok Kunstalle Budapest and accompanied by relevant conferences are necessary to facilitate a critical discussion of possible pathways for Georgian contemporary art, to find ways out of localism and joining a wider cultural discourse.

Ministry, Georgia-based project by Joana Warsz. Image courtesy: DESIGNTbilisi.

The younger generation of the Georgian artists is distancing itself from the Soviet past, but falls in the trap of exoticism, relying on enigmatic pull of Georgian folklore, ethnography, traditions. This is not dissimilar to happened with the other artistic traditions of the Eastern Europe that have difficulty achieving self-definition within a certain sense of inferiority.[34] One important caveat here is that this fixation on the national culture does happen in response to the Western gaze as well as curators, writers, cultural producers come to the country with already stereotypical premonition of finding a unique, but still a post-Soviet country.[35] Yet, it is up to the artists, curators, museums to change it. Observing Western discourse that considers wider themes and concerns of human existence be it merging of digital and physical bodies, nonhuman ecologies, or more socially engaged art[36] one realizes that further and deeper artistic, theoretical, philosophical analysis is needed for the next stage of development in the Georgian contemporary art to occur. And art schools, art publications, curators, art critics, art foundations, art centers have a responsibility to further push it.

Dematerialization of the art object as stated by conceptualism has also taken place in Georgia, but at times this conceptualism does not transcend formalistic foundations. Several talented conceptual as well as traditionally representational Georgian artists are currently working in Georgia, as well as in Germany, and the US, adding to the cumulative development of the contemporary Georgian discourse. They are collectively transcending the in-born local identities while in some cases successfully becoming part of the larger dialogues. As this process gains more momentum back in Georgia through visiting artists, extended critical dialogues,[37] international conferences, curators’ involvements, extended residency programs more Georgian artists will be able to effectively become part of the European cultural production once more.

Critical distance is needed for the further developments in the artistic practices. In Georgia artistic production already possesses theatricality, a heavy folkloristic element as well as far- permeating religious symbolism that all might be conscious or not, but all come from the temperament and shared history. What need to happen next is for Bertold Brecht’s ‘alientation effect’ to take place. According to Brecht and the premise of his theater creators of a spectacle use “techniques designed to distance the audience from emotional involvement in the play through jolting reminders of the artificiality of the theatrical performance”.[38] Artists need to become active and brave commenters on the society and the issues it is facing, without the immediate expectation of making their works viable or commercially successful. Commenting on social climate as well as immediate problems rather than self-exoticism for the export should be the new paradigm of the movement forward. One such example stems from 2010 performance titled “The Wet Circle,” when six graduates of the Academy of the Arts set down in a circle clad in white and took turns spiting at each other clockwise. This performance was greatly criticized by some and lauded by others, however, it most certainly reflects the common climate in Georgian arts and society when initiatives and progresses by one is often met by half-hearted and half-disguised derision[39].

Performance Wet Circle, 2010. Image courtesy: Keto Tsaava.

In order to cease being the Other for the rest of Europe at least, Georgian artists need to naysay their culture at least for a suspended episode of artistic practices, to create disruptive movements.

To pursue what notable Georgian writer Otar Chiladze derogatorily termed as “interest in hot themes, such as queerness, cosmopolitism, or globalization or in other words critique of the national culture and history.”[40] Right now, Georgia is underground a significant transformation of breaking down social, sexual and gender identity patterns and becoming more modernized version of itself. So, the Otherness of the traditional past is becoming even more pronounced and nuanced. Other is also us when removed temporarily (through time) from ourselves and the pain and disorientation we are experiencing in the time of transition is the pain of grieving our former selves. So in a way it could be argued that only now is Georgian culture and its visual, literary, cinematic art is going over this wound and developing a contemporary unique identity, synthesizing its troubled past with the present. Balancing Western-oriented narratives mirroring already well-known prototypes with a deeply personal in construction of the self rather than opposing the eternal Other, for the trajectory of Otherness to go another way. It takes time, but the process is underway.

III. Few strands of Georgian Otherness in New York

Every exhibition is, if you will, a montage in that it does not depict any real local context in which art functions, but is always artificial through and through. Boris Groys[41]

Ideally the goal of my exhibition in New York was to make people think through what personal narrative ‘you’ as a person are putting together and who ‘you’ are defining as the Other, to make ‘you’ aware of this process and as a consequence to consciously break that framework. By generating context while using critical framework the exhibition looks at what goes into the phenomena of psychological distancing. In the age of COVID-19 this might be even more petrinent.

Psychogeography used by Joachim Koester as part of his neu-archival approach to forgotten histories and figures is a very apt description of what my goal was for this exhibition. Rather than trying to connect two very different countries and cultures I explored them as two psychocultural entities with the desperate sets of believes, traditions, values, stereotypes. In doing this I am exposing and exploring narratives, some of them are more visible and some less so. These artworks are not touching, but being in a small space they are close to create intimate environments, like two people coming together to have a conversation, collaborating and becoming part of a larger discourse. In bigger sense the selection of this exhibition is about feelings and approaching the works in an emotional context.

One can choose an identity to embody here, in America and this is still what brings multiplicity of young individuals to scale the so-called American dreams. Yet, a process of transformation from one’s own born identity to what one inspires to become is a long, mostly painful process that takes a lifetime to complete, a comment heard from many artists in New York. In this transformation one is stranded between two versions of self, each with its own sets of expectations, codes of behavior, collective histories. A person needs to become the Other to her old self, while continuously proving that she belongs to her new aspired environment, with which she is yet not fully affiliated. This micro process is mirrored on the scale of a society as well. Mimicry of postcolonial societies to the Western codes of behavior, education, ethics, and culture illustrates this process. Georgia is another case in point.

Presentation of the works is reparative rather than confrontational. Twenty works represent talking points or signifiers of the issues to be addressed and are conceptually driven and contextually aware painting, sculpture, video, mixed media and text.

Tbilisi and New York both share certain cosmopolitan characteristics in terms of long history of being affordable places to live for artists, of wide ethnic diversity and a long tradition of at least explicit tolerance towards others. As in Brooklyn, it is extremely hard for emerging artists of Tbilisi to get adequate gallery representation even in their own country and even more so internationally. As a curator I looked for Tbilisi and New York artists who are underrepresented in their countries or in the West and with a few notable exceptions. It was important to me to find fresh take on the Other in a way that could transcend mere looking at two or more different artists within a medium into a more insightful experience and make us ask questions how we create, use, mitigate Othering as a verb, how we as species came to rely on this mechanism for our survival, why we cannot create a more wholesome intrinsic image of ourselves that would not require projection of our fears and insecurities upon an outside entity.

What are the ways to respond to the Other? The negative connotation of this noun is so deeply ingrained into our psyche that response always tends to start on a negative note of Fear/anxiety. Rita Khachaturian explores fear in her series of smaller-scale portraits and is fascinated by what people are afraid of. A woman is afraid that she would not be able to accomplish her calling, but is not yet sure what that calling is. A man is afraid of a betrayal. A woman is afraid that there is no god, while a man is afraid what kind of reaction his laugh produces.

Andy Ralph’s mirror invites a viewer to look at herself and contemplate her own narratives in three disparate parts.

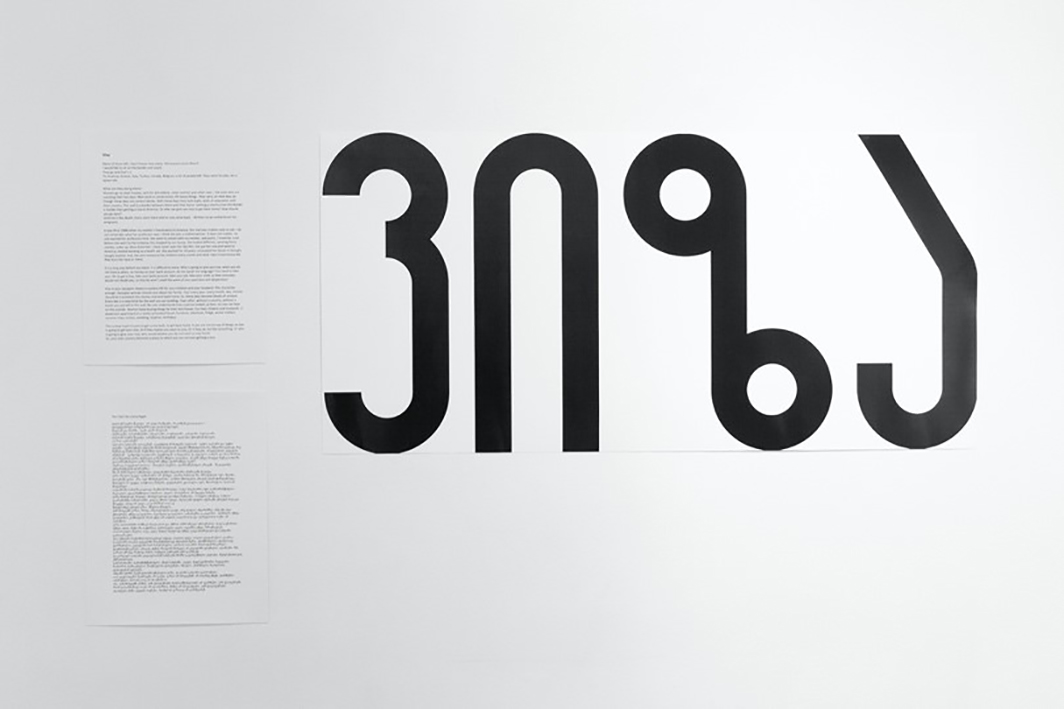

Mariam Natroshvili and Detu Jincharadze’s conceptual text work Visa references the Georgian word for it, presented together with a text written specifically for the exhibition. In it the artistic duo explores language in multiple modalities. Economic migrants who are part of the economic force, never become full-fledged members of society are in the center of this work. Natroshvili works with the Georgian alphabet, unique to that part of the world and completely baffling to the outsiders.

Dana Levy piece whose video piece Eden Without Eve was shot in Everglades and looks at our fear of the Other from the environmental and psychological standpoint. Snakes and people habitually living with them feature heavily in this metaphoric work, reminding of old religious symbology. Old religious symbology is also element of Mikheil Sulakauri’s work Upper East Icons, as it portrays an old mystical ritual of brewing wheat as part of venerating local god of the sun in the remote region of Georgia, Tusheti. These two videos also talk on a different level as outsider local cults of Sulakauri are metaphorically transplanted by religious uniformity of Levy’s context.

Mariam Natroshvili, Visa, 2019. Image courtesy: Kunstraum LLC.

Sometimes the Other awakens an erotic infatuation in us and this is something explored in both Tim Foley’s work centered around queer identity and Anuk Beluga’s sculpture Celebration that both accentuate our intrabody connection. Yet, on the personal scale how could we approach Otherness? Intimacy and love could be one route. But here we also encounter difficulties as recognizing the other would be about dominating. Jan Verwoert describes the slippage between love-as-recognition and love-as-control in an essay called “Masters and Servants or Lovers: On Love as a Way to Not Recognize the Other.” [42] In which he tries to convince us that to love another we simply need to not let them know us.

Tamara Kvesitadze and Shiri Mordechay both portray women as Others, traditional objects of male fantasies. However, both artists explore this motive of otherness in a contemporary reality. Kvesitadze uses watercolor to highlight the sensual and earthy abstract portrait of a modern woman who might terrify a modern man with her inner power. Mordechay uses techniques of innocence, of an almost naïve fascination with what is hidden. Desire to dominate is another common response to the Other as shown in videos Nino Beniashvili who looks at requisites of women’s role in Georgia, Israel, and Sweden.

Giorgi Rodionov looks at the Soviet Other as part of contemporary Georgians. Name of his project, from which the two photographs are chose is telling, My Parents Don’t Talk to Me.

Rusudan Khizanishvili and Juliana Cerquiera Leite both are concerned with post-colonial and feminist contexts of Otherness. If Khizanishvili uses archetypal forms to become part of the Western ideology, Cerqueira Leite criticizes Darwin’s concept of survival of the fittest and uses elements of abject art to show subordinated power dynamic.

This is a very brief overview of the works as I tried to present a few contemporary Georgian artists in a microcosm, some of them use self-exoticism, but most are looking for their ways. This reflects the larger story of the contemporary Georgian art.