Black Ice

‘Belfast, I live and breathe you. Belfast, you are etched deep within my soul. Belfast I have become you and carry the stink of your corpse like a cause’. A.F.N. Clarke (in Aaron Kelly, p. 173)

During a very British breakfast in the dining room of a B&B in North Belfast, lit up by Nordic winter sunlight, I was chatting with my travel companion, probably trying to convince her to eat something, in the minimum respect for a tradition that seemed very important in those four walls. But she by then had already taken on the wrong attitude, of closed-mindedness, of disgust. Her judgments were becoming ever more frequent and biting, especially when compared to my enthusiasm. In fact, they often followed immediately after my joyous exclamations in a clear and shrewd way. More than judgments, they were prejudices. I understood this. She, perhaps, never understood.

I realize that I can go overboard with my enthusiasm, but she seemed to want to kill it before it even took form. But I had already been through that. I had been born with that kind of mental closure, in the guise of healthy reason. By then, however, I was back in touch with myself and I had no intention whatsoever of leaving again. That enthusiasm was the first clue to my true realization.

The history of the island of Ireland consists of several phases and is characterized by countless military invasions by external populations. Wikipedia

From the window I see a couple go out from the entrance of the B&B.

The Viking invasion and extended stay, however, did not change the religious attitude of Ireland… Wikipedia

The woman, as soon as she puts her foot out the door, slips and falls to the ground.

The particular geographic proximity of Ireland to Great Britain has always favoured the presence of the English on Irish soil.

The first significant contact between the two peoples came in 1170, when a group of Normans from Wales arrived in Ireland, with devastating consequences to the Gaelic world.

Very soon, however, the Normans assimilated into the culture of the place. Michela Arienti (p. 5)

They call it Black Ice. A treacherous ice, because it can’t be seen.

It was the last day of our short stay in Belfast.

On that very day, I had decided it was necessary to begin to understand and we plunged, with a useless map, into the North of the city.

Maps petrify the potential for historical transformation. By rendering a cultural space static, they are inherently past-tense, because the present, for Carson, is dynamically open to the future… Alan Gillis (p. 185)

We walked very slowly, grabbing onto whatever we found along the way: grates, gates, trees.

The English kings tried in vain to stop the process of assimilation, even stopping mixed marriages, prohibiting the adoption of Irish clothing and hairstyles, the use of Gaelic and the use of Irish law by those that were considered “Englishmen born in Ireland”. M. A. (p. 5)

The situation was really peculiar. Beautiful light. Snow on the peaks around the city. The constraint of a careful step and watchful eye. The very few cars on the road went even slower than we did. Very often, however, we met children who played happily on those slippery paths, taking advantage of the ice.

The Gaelic Irish and the old English, in any case, did not convert, but continued to profess Catholicism and opposed the officials of the Crown and the English settlers recently arrived on the island. M. A. (p. 5)

The night before, I had checked online for the right streets to take or, better yet, where to find the Peace Lines, the famous barriers that divide the Protestant communities from the Catholic ones.

No one, in fact, despite our requests, had brought us to see them yet.

The vast balk of those who had never known a life in Belfast without the Troubles, simply switched off. They effectively dumped the past and now inhabit the strobe-lit present with extraordinary fervour: and who would blame them? Gerlad Dawe (p. 201)

At the time, I was only at the beginning.

Even today, I’m surprised to discover how many kinds of walls and how many zones there are, how many areas can’t be crossed.

Everything is so fragmented and really incomprehensible for a foreigner, especially on the first visit.

In the Troubled Times of three to four centuries ago, the then town was fortified: girt about with stone-faced walls, twenty feet high, with inner wall-walks, guarded gates, and polygonal bastions. Although these walls were, by degrees, dismantled over the years at the instance of over-optimistic men of commerce, they have in more modern Troubled Times reappeared in slightly different guise, but along almost precisely the old lines. Now they take the form of tall steel arrow-tipped railings, topped by coils of barbed wire, interrupted at intervals by heavily padlocked gates for ingress; and clattering seven-foot turnstiles for egress; so that the innermost circle of the city can be garrisoned, isolated, and protected from intruders.

There are, scattered throughout the City, other defensive structures of various kinds and degrees of permanence. At some periods, the citizenry in their embattled enclaves have built barricades of paving-stones and cars, lorries and omnibuses, often burned or burning, around the sacred boundaries of the indicated territory. Such obstacles have mostly been transitory. More permanent, more linear, are the Eirenic Walls staking out the boundaries between tribal homelands. Sometimes, these are high corrugated-iron fences. In such cases, they may (on both sides) provide the groundwork for the embellishments of graffitists. Elsewhere, they have become genuine walls, usually of brick, often as much as fifteen feet high, usually treated with some form of surface graffito-deterrent; intended accordingly to shield and protect those who must live, so to speak, in the shadow of the wall, from the greater exuberance and pugnacity of those who live on what must be (by definition) its upper side. Albert Rechts (pp. 13-14)

Later I understood that I would never completely comprehend. But I have always felt a great empathy for the city and partially, piece by piece, I started to grasp it, even if, just when I am most sure, everything gets away from me again and becomes confused.

This chaos, this blurred vision, this puzzle seems to compose itself in a different way every time. But I’m starting to put the crucial points into focus. Maybe.

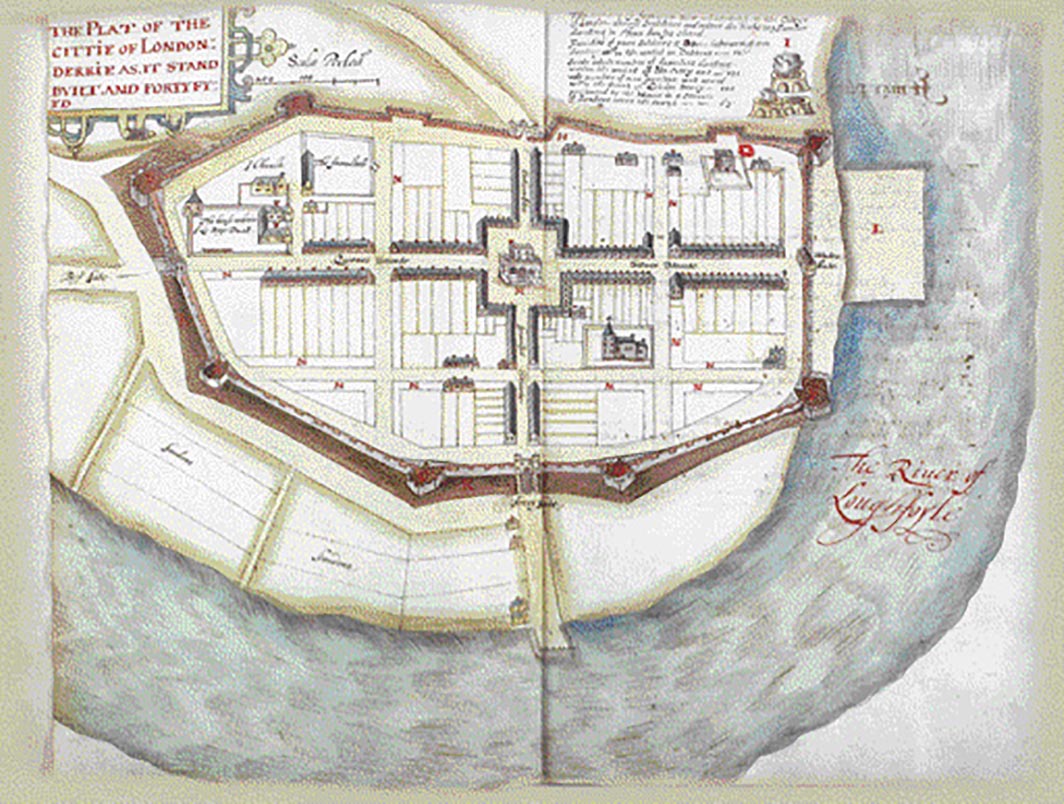

One of the events that has most influenced Irish history up to the present was the so-called “Plantation” (1608-1610), the systematic transfer of English and Scottish settlers into various zones of Ireland in order to consolidate English rule. The new settlers, mostly Protestant, were placed mainly in the Counties of Tyrone, Donegal, Derry, Armagh, Cavan and Fermanagh (Ulster), depriving the local population of the lands and forcing it to take refuge in the hinterlands. M. A. (p. 5).

The first time, I just flushed out – stubbornly, given the hostile day, and surrounded by indifference – which streets could absolutely not be missed. I headed towards Shankill Rd, with the help of the map and with a travel companion close behind who, perhaps, that very day decided that she would never again be submitted to such a systematic study of suffering.

I, however, had missed it. I had been atrophic and anesthetized for too long.

The walls of the City of Derry-Londonderry were constructed between 1613 and 1618 to protect the English and Scots settlers in the new town that was established here as a part of the Plantation of Ulster.

James I of England ordered this colonisation of Ulster with loyal, Protestant subjects in order to bring this rebellious Gaelic region firmly under the control of the English crown, following the defeat of the Gaelic lords in the Nine Years’ War (1594-1603) and the Flight of the Earls in September 1607. NIEA’s Guide (p. 3)

That condition has never been part of me. Above all, I have especially always known that it’s not good for you; that sooner or later the traumas, if removed, will re-emerge. You can’t sedate them, in fact, you must dominate them.

In 1611 The Honourable The Irish Society was founded to take charge of the plantation, and in particular to oversee the settlement at Derry, and financing was obtained from the City of London to build the walls. Today the walls are still owned by The Honourable The Irish Society. NIEA (p. 3)

And here we are.

We are in front of the Crumlin Road Courthouse. I found out a lot about this place afterwards, including how they are desperately trying to sell it. Obviously they can’t.

It is the picture of everything. Walking along side it, observing it in its abandon, in its wounds, it seems to be overcome by a huge amount of sentiments and sensations: uneasiness, curiosity, suffering, anger.

The silence around it is deafening. That ice and that light make that moment unique, the start of my affection for this place.

In 1641, a rebellion broke out in Ulster, organized by the Gaelic Irish and the old English, Catholic, in order to recover the lands that had been expropriated from them. The revolt escalated into violence and brutality against the English settlers. It was a historically important event: for the first time, Irish Catholics had risen up in the name of the Catholic cause. The division between the two communities of different religions was emerging. M. A. (p. 6)

We carry on. We find ourselves very near Shankill Rd. We are struck, again, by the absence of humans. Then, by the types of houses. Then, by the many churches that seem to be closed.

Again the picture of something escapes us, from a time we don’t even know.

In August 1649, Oliver Cromwell disembarked in Ireland and violently took control of the island. It is estimated that, in his raids, more than a quarter of the Irish population was massacred. The lands owned by the Irish were expropriated and distributed among English soldiers and the new settlers, while the Irish were forced to emigrate west of the river Shannon (Act of Settlement).

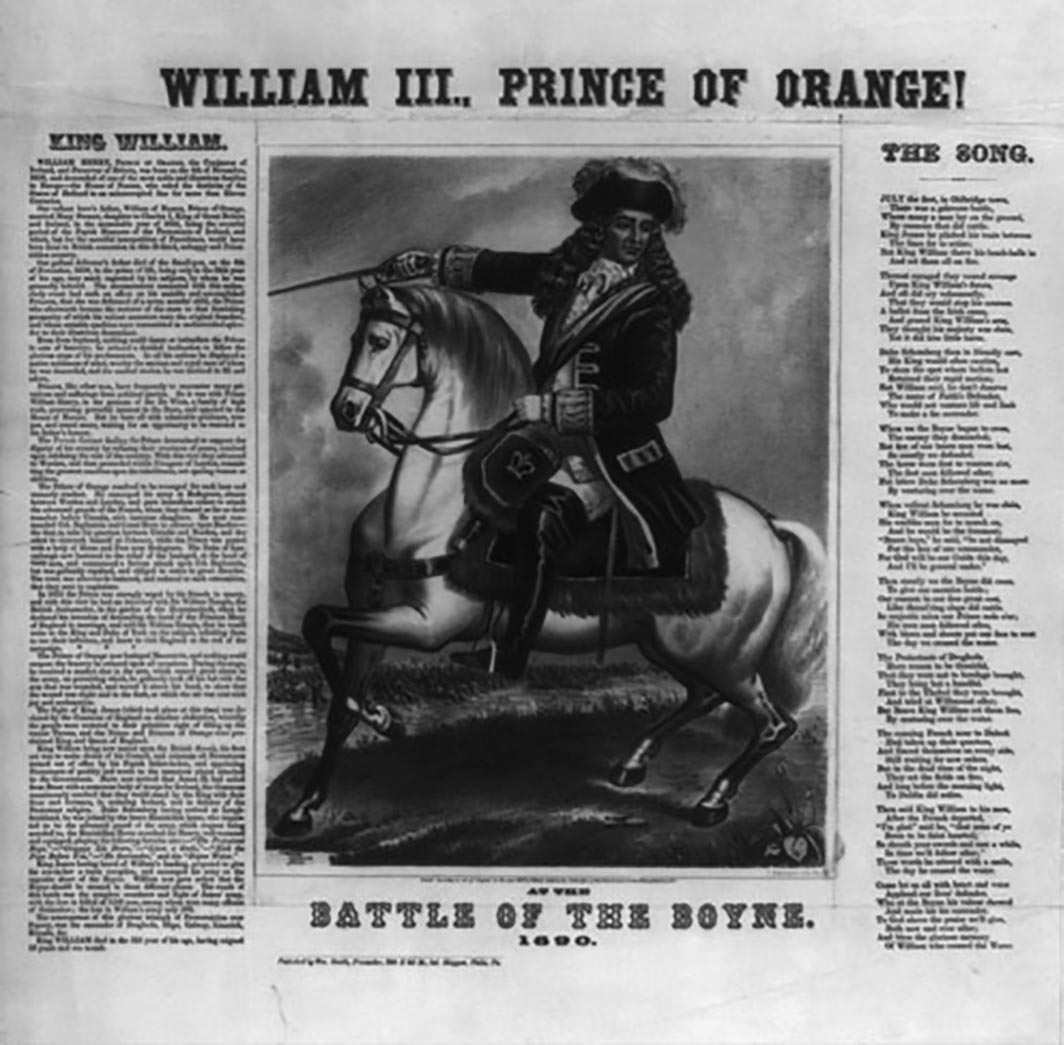

The subsequent victory of William of Orange over James II, the Catholic King, had a catastrophic effect on the lives of the Catholic community: at the beginning of the 18th century, only 14% of land belonged to Catholics and, through the “Penal Laws”, they were denied access to property or political power. M. A. (p. 6)

We desperately want to take a break. To stop for a moment. To rest our legs and our eyes.

In what seemed to be a neighbourhood literally without a soul around, we enter a prefab and find ourselves in a place where there is everything: cafés, a theatre… and, above all, people, mostly children and teenagers. Is it a parish?

The Battle of the Boyne was fought in 1690 between two rival claimants of the English, Scottish, and Irish thrones – the Catholic James VII & II and the Protestant William III and II – across the River Boyne near Drogheda on the east coast of Ireland. The battle, won by William, was a turning point in James’s unsuccessful attempt to regain the crown and ultimately helped ensure the continuation of Protestant ascendancy in Ireland.

The battle took place on 1 July 1690 in the “old style” (Julian) calendar. This was equivalent to 11 July in the “new style” (Gregorian) calendar, although today its commemoration is held on 12 July, on which the decisive Battle of Aughrim was fought a year later. William’s forces defeated James’s army of mostly raw recruits. The symbolic importance of this battle has made it one of the best-known battles in the history of the British Isles and a key part of the folklore of the Orange Order. Its commemoration today is principally by the Protestant Orange Institution. Wikipedia

Great fires are built, too, as a mode of communal celebration.

At certain seasons, and at the time of certain feasts, these fires assume astonishing proportions.

However that may be, on a stated name-day, throughout the Mongol quarters of the City, enormous bonfires blaze all night at every street corner.

Their construction takes many weeks: they may tower twenty or thirty feet tall, built by children and adolescents of the quarter out of old chests and boxes, beams and rafters, motor tyres, broken furniture and strayed sofas, paper, and the branches or even trunks of growing trees.

Small boys, fallen asleep on sentry-duty, are in many years thus roasted alive in their nests.

In most years, a perceptible number of citizens – adults, adolescents or children – will be mutilated, or charred, or lose their lives, or their homes, or their belongings, as a result of these bonfires (or malfires). A. R. (pp. 31-32)

We go on, following the map.

We want to see the other street, of course. Falls Road.

The failure of a revolt organized in 1798 by the United Irishmen alarmed the London government, which then decided to abolish the Irish Parliament.

Through the “Union Act” (1800), Westminster regained the power to legislate on Irish matters. M. A. (p. 7)

We turn the corner and, astonished (this time she is, too), we find ourselves in front of a wall.

The first Belfast wall that I saw is one of the most disturbing and violent.

Tall, dark, long.

The map shows streets that, in reality, are quite clearly broken.

Around us, there are many small fenced areas, in a clear state of neglect.

We nearly panic. Now what do we do?

Daniel O’Connell, who in 1823 founded the “Catholic Association”… M. A. (p. 8)

We encounter reality, more absurd than a dream.

A taxi stops in front of the wall and lets two tourists out, who take photographs in front of a few famous murals and leave again.

We chase after the taxi. It stops. We ask the driver how to get to the other side.

He tells us simply to follow the wall; at some point we would find a gate.

And so it was.

An enormous gate with the doors open.

Between 1845 and 1849, the island was hit with famine: more than a million Irish people died and many others emigrated, all to the indifference of the London government. M. A. (pp.8-9)

In fact, in the late afternoon, they still close them.

The fear of losing privileges they had enjoyed up to then made the Protestants organise a Convention, in which they declared themselves against any attempt to break the bond with Great Britain. The Unionist Movement was born.

James Connolly organised the Irish Republican Socialist Party and Arthur Griffith founded the newspaper United Irishman, which supported the theory of the so-called “Sinn Féin” (Only Us). M. A. (pp. 11-12)

Some of them don’t even know, they deny the reality of where they live.

It’s true however, even though there are no longer police around the gates, the doors are closed every evening.

The unionists were opposed to any form of self-government, fearing, through the creation of the Ulster Volunteer Force (the paramilitary branch of the Orange Order), even the use of armed force.

The pressing threats of the unionists made the London government nervous, and it agreed, with the support of the conservative party, to exclude the six Counties of Ulster, where the Protestant population was largest, from the application of the Home Rule.

Not all the nationalists accepted the political compromise proposed by the Irish parliamentary party, and a group of dissidents created the Irish Volunteers, better known as the Irish Republican Army (I.R.A.) M. A. (pp. 12-13)

IRA, 1922.

The gates are closed every night.

And I have to repeat it over and over, to accept it.

Just like all the other things that are considered normal here.

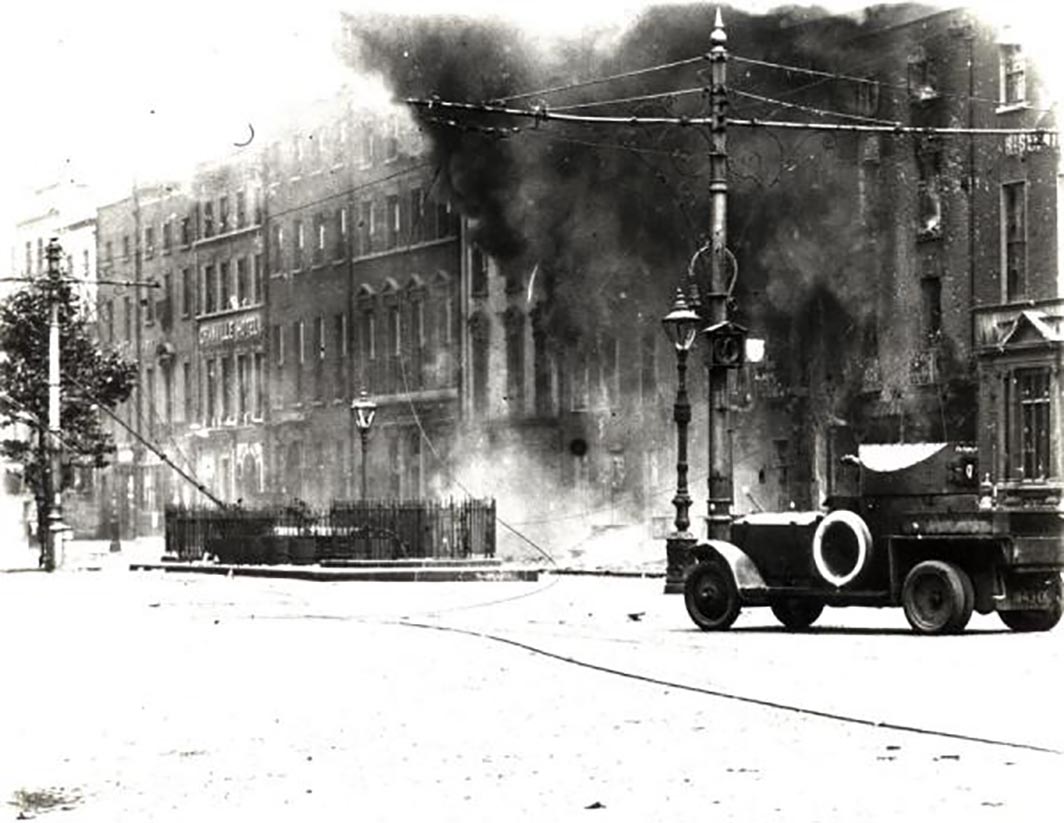

April 24, 1916 was a crucial date in Irish history. Some revolutionaries, led by James Connolly and the poet Padraig Pearse, staged an uprising in Dublin, known to history as the Easter Rising.

The news of the death of the leaders of the revolt stained the conscience of the people…

Many nationalists abandoned their support of the parliamentary party and joined the Fenian cause. M. A. (pp. 13-14)

Dublin, Easter Rising, 1916.

To go to Donegal, a coastal region of the Republic of Ireland geographically located to the North, they say: let’s go South.

It was a commonly heard and wearisomely repeated joke in Derry in the 1930s that people heading to Inishowen, the most northerly part of Donegal, would say, ‘We’re going south politically but north geographically’. Sean McMahon (p. 13)

They have several kinds of North Irish pounds.

In 1918 general elections were held and the Sinn Féin, under the leadership of De Valera, won seventy-three seats, against twenty-six won by the unionists.

Following pressure from the liberal party, the government issued the Government Ireland Act in 1920, which dictated the division of the island into two separate legal entities and the institution of different parliaments and executive branches. M. A. (pp. 14-15)

Derry is so close to the border with the Republic of Ireland that after just 2 kilometers, the euro is used. A text message pops up on your mobile phone with the enthusiastic announcement that you are in Ireland!

[The First] Bloody Sunday was a day of violence in Dublin on 21 November 1920, during the Irish War of Independence. In total, 31 people were killed – fourteen British, fourteen Irish civilians and three republican prisoners.

The day began with an Irish Republican Army (IRA) operation organised by Michael Collins to assassinate the Cairo Gang, a team of undercover agents working and living in Dublin. Twelve were British Army officers, one a member of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) and the last a civilian informant.

Later that afternoon, Black and Tans of the Royal Irish Constabulary, supported by members of the Auxiliary Division, opened fire on the crowd at a Gaelic football match in Croke Park, killing fourteen civilians. That evening, three IRA suspects in Dublin Castle were beaten and killed by their captors, allegedly while trying to escape. Wikipedia

We go through the gate and we are in Falls Rd., on the other side.

On December 6, 1921, the Anglo-Irish Treaty was signed, which established that twenty-six of the thirty-two Counties that would make up the Irish Free State.

As for the six Counties located in the northeast of the island, the sovereignty of the Irish Free State was suspended pending the decision of the population, earmarked to be two thirds Protestant, as to whether to adhere to the new State. The will of the people was expressed against this possibility and, in 1925, the Boundary Commission confirmed this choice.

The Irish negotiating team who signed the Treaty.

Michael Collins is in the centre, with his head down.

Ireland was divided. M. A. (p. 15)

That same day I returned to Rome.

My heart stayed on there, in that space between Shankill and Falls, between Protestants and Catholics, between the murals, between the memorials with dates and names unknown to me, slipping and sliding on desolate streets, surrounded by breathtaking nature.

‘Belfast, I live and breathe you. Belfast, you are etched deep within my soul. Belfast I have become you and carry the stink of your corpse like a cause’. A.F.N. Clarke

(in Aaron Kelly, p. 173)