On the Lack of Backbone (Changing the Viewpoint)

Essay on the practice of the artist duo nabbteeri written in conjunction with the five-year Frontiers in Retreat project (2013–2018) organised by the Helsinki International Artist Programme HIAP and seven other European artist residencies.

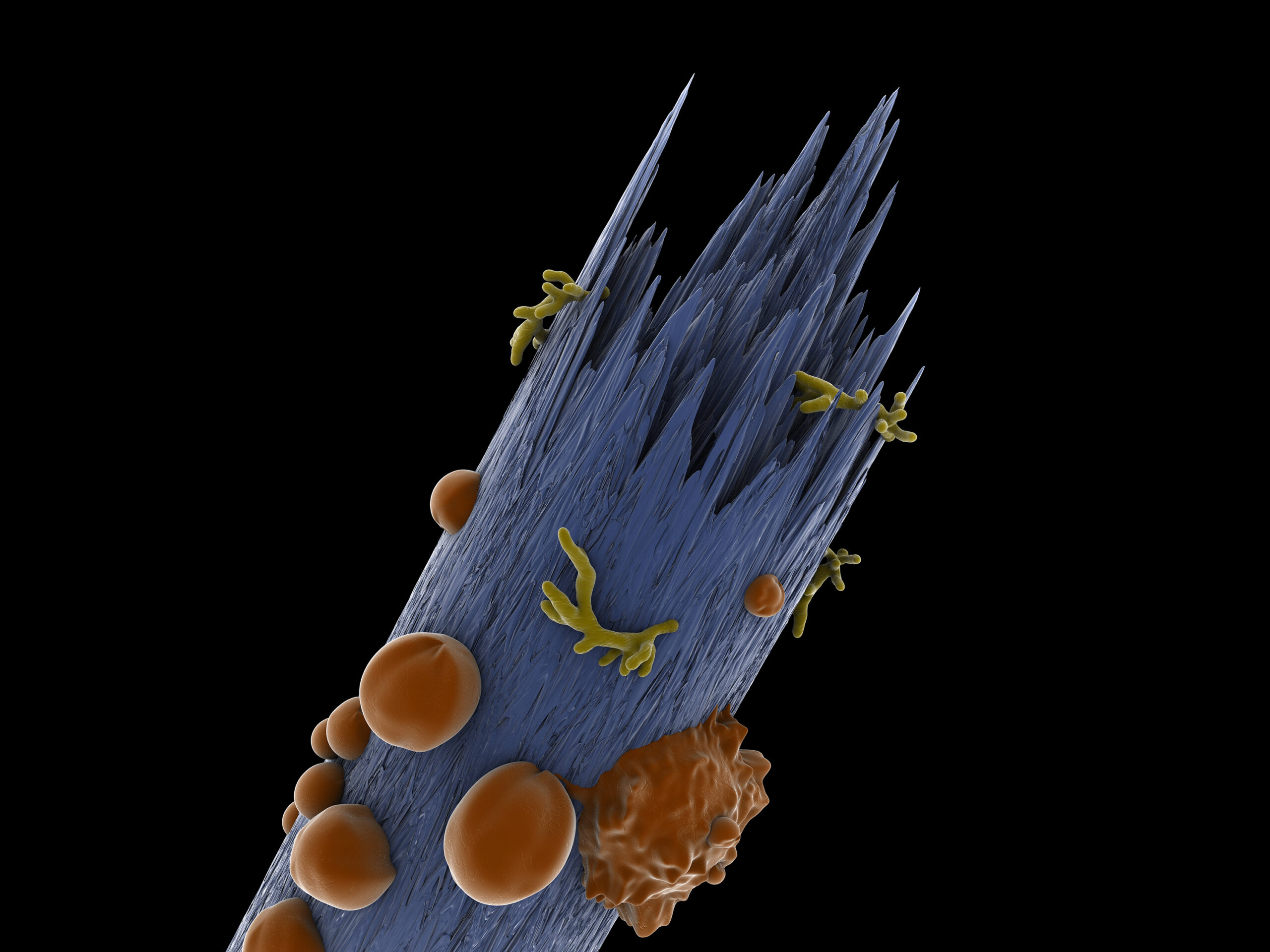

nabbteeri, Thinking of Invertebrates, 2017, still from a 3D animation

HD, loop, duration 30 min 16 s. Photo: nabbteeri

Someone has been here. Or perhaps more accurately, it would seem that a whole legion of critters has been here. After a short while spent in the space I’m certain that I can hear rustling, and it feels as if there’s movement at the edges of my field of vision that disappears as soon as I try to look directly at it. The absent presence of life invokes an uncanny feeling that stays with me for weeks.

The artist duo nabbteeri (Janne Nabb, b. 1984 and Maria Teeri, b. 1985) has a talent for creating spaces that set off thoughts. This time the space has emerged in Turku’s Titanik gallery under the name Mapping the Insignificant (2.–25.2.2018). One has to talk precisely of spaces when it comes to nabbteeri’s works, because the entities that the two create are not exhibitions in the traditional (modernist) and static sense of the word: nabbteeri always constructs an entire environment that is to be experienced from the inside and internally rather than disinterestedly admired from a distance. The artworks are also rarely distinctly standalone pieces, rather melding into one another forming broader, discursive spatial wholes. As such the duo’s art also reflects their authorship as artists, which doesn’t revert back to one individual alone. And thus, the show in Titanik is also made up of four works of art but to tell them apart one has to use a map[1] provided in the exhibition handout. Thinking of Invertebrates (2017/2018) forms the backbone of the whole into which Fallouts (2017), Blackout (2018) and Whiteness (2018) seamlessly intertwine.

Mapping the Insignificant is an outcome of the artist duo’s partaking in the five-year Frontiers in Retreat project. The aim of the joint project by Helsinki International Artist Programme (HIAP) and seven other European artist residencies[2] was to consider and outline new approaches to ecology[3] through the means of contemporary art. Between 2014 and 2017, nabbteeri visited four artists’ residencies in connection with the Frontiers in Retreat project. From each residency, the artists picked up something new to take with them, whether it was a new crafts skill, experience, or a physical object. And now, all the time that flowed during those residencies has been condensed into the art works engaged in a dialogue in Titanik.

The ensemble on show in Titanik is a somewhat unusual occurrence in the history of nabbteeri’s artistic activity. Previously, the duo has favoured a site-specific method of working that has been distinctly material. Their pieces have been made from objects, items and waste[4] found at the exhibition site, thus making the dependency between the site and the art work wholly evident. For instance, the canopy of the installation Paviljonki (Pavilion), executed for the Mänttä Art Festival of 2012, was made up of old inner tubes for bicycle tires found in the storage of Pekilo, the legendary exhibition space and former fodder factory. In the process art piece mesh/mɛʃ/ (2015) for Espoo Museum of Modern Art EMMA, the artists used materials found in the museum. This was in itself necessitated by the climate-controlled conditions of the museum institution that do not allow for foreign objects[5] to be brought in without a time-consuming quarantine. Even when the duo was awarded the Young Artist of the Year award in 2014, they created works for the accompanying award show, traditionally executed in a somewhat retrospective manner, by using materials from the museum that housed the exhibition: the Tampere Art Museum. Often, of course, the pieces also include equipment brought from somewhere else, like the expo stands that have taken a role in multiple pieces or the watercolours made in the studio, not to mention the video works that are by their very nature siteless. But something has always connected the works to the exhibition site on a material level. The works that congregate in Titanik have, however, all been created somewhere else. And yet these pieces are site-specific, too; it’s just that the site doesn’t happen to be this particular gallery, but rather the Frontiers in Retreat artist residencies. The matter is elucidated by the notion of focal practices.

nabbteeri, mesh /mɛʃ/, 2015, exhibition view

EMMA, Espoo Museum of Modern Art, Espoo, FI. Photo: nabbteeri

nabbteeri spent their first Frontiers in Retreat residence period in the Catalonian village of Farrera. Here the artist duo decided to put into practice the idea of focal practices, a notion that is based on the concept of Albert Borgmann and that has been developed further by Antti Salminen and Tere Vadén. These practises build on local traditions that span generations. As Salminen and Vadén write in their book Energy and Experience (2015), by slowing down and nurturing that which is close to us and particular to the local culture, we can challenge the homogenisation of localities[6] that has been brought about by fossil capitalism[7]. The artists themselves admit that it is almost paradoxical to take on an exercise that calls for longevity, often transcending generations, during a two-month residency. But positioning themselves in relation to the site and the locality was precisely what made the residency meaningful to nabbteeri. Slowing down is also a key feature in artisanship, which has always been central to the artistic practice of the duo: learning and honing a skilled and time-consuming craft requires the ability to deliberately pause and concentrate.[8] Focal practises and new crafts learned are visible in everything in Titanik, where one can find, for instance, an adaptation of a Serbian kuvarice textile[9] (2016, FiR residence Cultural Front GRAD, Belgrade, Serbia), an impressionistic rya made in Suomenlinna (2017, FiR residence HIAP, Suomenlinna), and two interpretations of the Korean bojagi wrapping cloth[10] (FiR project’s nomadic exhibition Edge Effects was featured in the Art Sonje Centre in Seoul, South Korea, in 2017). The 3D animations, in turn, represent a kind of nomadic craft and their skilfulness could perhaps be described as techno artisanship. All in all, the mapping of the insignificant seems to be about slowing down and meticulously studying the local culture. But the culture being mapped is not merely human. Let us return to the critters that remain unseen.

Dust mites no longer exist. At least not in Finnish homes.[11] This is what I’m thinking about as I watch the video that is part of the Thinking of Invertebrates piece, and out of which my gaze picks out a 3D modelling of a microscopic invertebrate that resembles a dust mite.[12] We’ve air-conditioned, scrubbed, and hygienicised our homes so efficiently that this small organism can no longer cope in the human-governed environment. Not all invertebrates have, however, given up in the face of ever more inhospitable environs, but have rather adapted to the times and customs, like the larvae of the carpet beetle that has taken to munching on clothes, and against which a ruthless chemical warfare is being conducted in households. In Thinking of Invertebrates, the larva poses in two ryas realised on mesh shirts. It is somewhat sweetly ironic that the larva, in Finnish known as “fur beetle” and traditionally infamous for eating and thus destroying furs, has been immortalised on the substitute for fur, that is, the rya. The less-well-off section of society used to line their sledges with ryas,[13] and today, the cycle becomes complete in the wealthy neighbourhood of Töölö, where the wool used for ryas has also turned out to be a delicacy of the larvae.[14]

The video for Thinking of Invertebrates is a twofold travel diary made up of notes read out loud and of visual observations and associations. At times, these two travel diaries synchronise only to continue on again, governed by their own logic. The video becomes a lingering homage to invertebrates that make up 97% of the wealth of animal species, as the molluscs and arthropods embroidered on a kuvarice towel inform me. Inevitably, encounters with the remaining three percent have also been recorded in the travel diaries. I wholeheartedly identify with the moments of connection and understanding described in the diaries that encountering another living creature produces in us, and the sense of wonder that observing them brings about. And yet, especially the visuals of the video have a melancholy undertone. A disembodied tentacle writhes in the throes of a macabre dance, and I can’t help but think about how the severed tentacles of octopi act almost like reversed phantom limbs: even after an hour, they’ll reach out for food and try move it toward a mouth that is no longer there.[15] The animations have an atmosphere of an end of the world with water rising and a flare lighting up a deserted landscape. Or perhaps these are images of a possible future, for many of the throbbing invertebrates on the video appear to be as of yet unknown species.

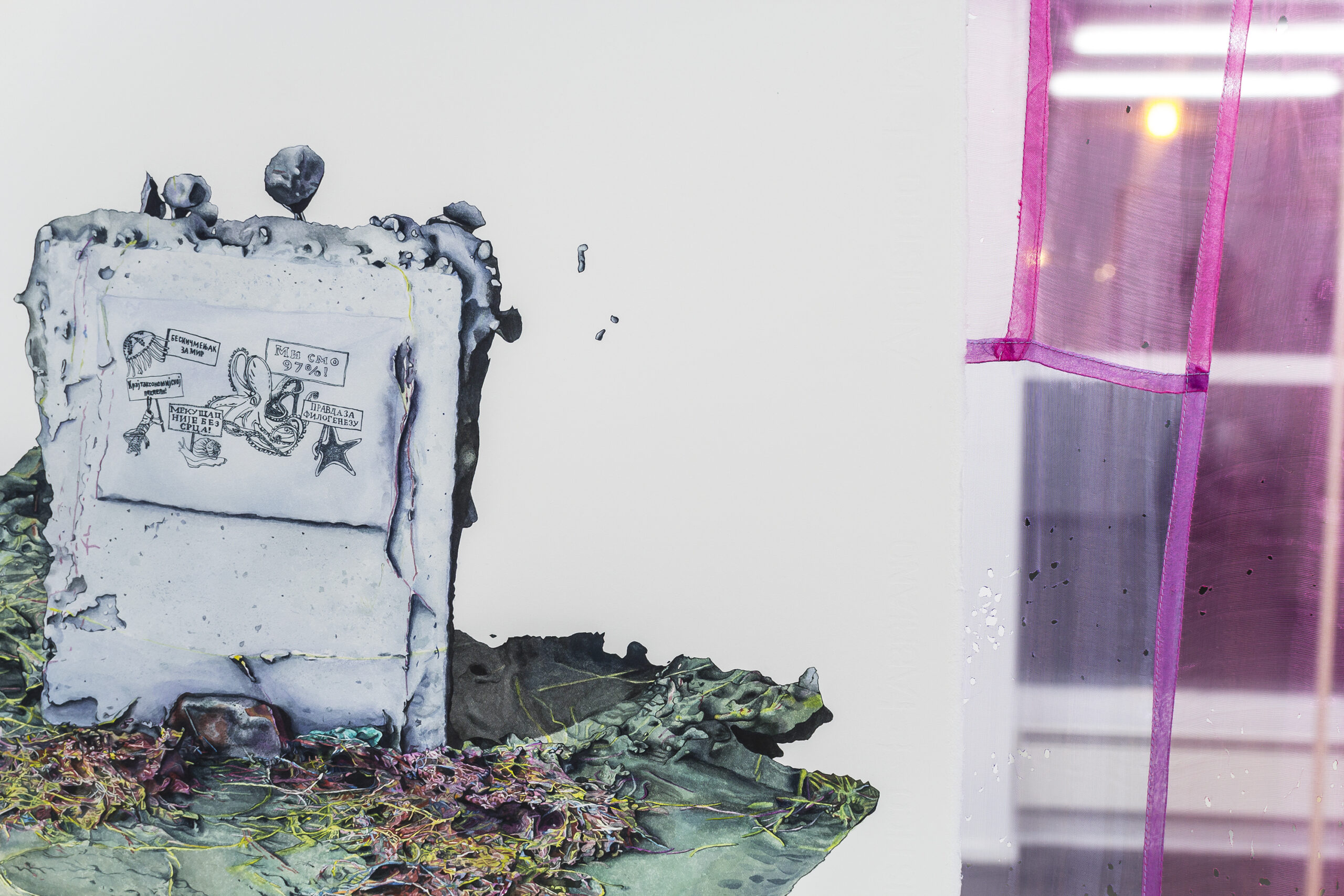

nabbteeri, Mapping the Insignificant, 2018, exhibition view. Titanic Gallery, Turku, FI.

In detail view: an unfinished handwritten copy of Donna Haraway’s article published in e-flux in September 2016. Photo: nabbteeri

Time and again I return to examine the bojagi adaptations that have been chewed full of holes, and the expo divider with intricate patterns that deceitfully resemble those etched by bark beetles on the vascular cambium layer of trees. The exhibition handout reveals that these are the doings of another creature from the future: the plastivore. A real-life plastic eater would beat everyone from carpet beetles to rats[16] in tenacity and adaptability, since the ability to eat plastic in this polyethylene-saturated world would undoubtedly be an advantage like no other: food would be available in abundance, as every year some 80 billion tons of polyethylene, the raw material of plastic, is produced. One wouldn’t have to worry about a use-by date either, since it takes between 100 to 400 years for a plastic bag to decompose. Although a few genuine plastic eaters[17] have indeed been discovered in the ranks of invertebrates (for example, the larvae of the honeycomb moth and the mealworm produce enzymes that break the polymer chains of plastic[18]), a plastivore is still a mythical creature. And still (or perhaps precisely because of), the cape of humanity’s saviour is being fitted on the shoulders of these little plastic-eating critters, because instead of changing our ways, we are intent on finding a backdoor so that we might hold on to our convenient existence[19] a little while longer.

The watercolour series titled Fallouts (2017) carries thoughts ever deeper into plastic. I seem to recognise many mundane items in the excruciatingly precise still lives: floorball halves, the handle of a walking stick, the plastic cap that seals the fuse of a firework. The dystopic but brutally realistic visuals of the series put the environmental effects of plastic on par with the fallout from nuclear explosions, which can take the form of radioactive dust or black rain that can travel for hundreds of kilometres, weather conditions permitting. The fallout from plastic[20] may turn out to be just as serious, if not even more devastating than nuclear fallouts, since unlike nuclear power, the production and use of plastic is still poorly and inconsistently regulated. [21] I cried when David Attenborough told of a dolphin calf that had died as the result of the plastic-related toxins accumulated in its mother’s milk. [22] What can be done?

nabbteeri, Mapping the Insignificant, 2018, exhibition view. Titanic Gallery, Turku, FI.

In detail view: watercolour on paper from a series of photogrammetrical postnuclear studio views, and adaptation of traditional Korean patchwork craft that has been devoured by speculative plastivorous critters. Photo: nabbteeri

I believe that this is precisely what Frontiers in Retreat is about as a project, and that Mapping the Insignificant is nabbteeri’s response to the question. The scientific community is currently debating whether we have entered a new geological epoch and if this new epoch should be called Anthropocene – meaning the era of humans. Wouldn’t the titling of an entire geological epoch after ourselves be the most self-involved thing we could possibly do? This, among other things, is what Professor Emerita Donna Haraway ponders in her essay Tentacular Thinking: Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Chthulucene (2016), an unfinished handmade copy of which also hangs in the window of the Titanik gallery. At times Haraway is associated with post-humanism that follows similar paths of thought to deep ecology: we must abandon our human-centred thinking and cease to see the Earth and nature as disinterested resources that we can take advantage of without a care for our fellow beings. We do not exist in isolation from other organisms, but rather live every moment in a concrete symbiosis with, for instance, bacteria, which we need for the maintaining of our lives.[23] Perhaps instead of a continuous expansion of borders (frontiers), we ought finally to pull back (retreat) and give nature space to breathe and realise its own existence. And yet, a return to some kind of virginal state of nature is no longer possible, neither can we simply leave nature to fend for itself. Instead, we must accept our roles as nurturers and caregivers. This calls for a change in viewpoint, and that’s precisely what mapping the insignificant is about: life bustles everywhere, if you simply stop to look, like nabbteeri has done. And that wondrous, beautiful, and ever-changing life is threatened from multiple directions, if we totalise it into a commodity and refuse to see its otherness as an intrinsic value. For we lack backbone: in our current state, we are ethically irresponsible, but also literally related to invertebrates.[24] Therefore, it is high time we positioned ourselves side by side with rather than above other organisms. As Haraway puts it: “Nothing is connected to everything; everything is connected to something.”[25] – we must start with what is nearest to us, we must map even the most insignificant.